Туннель любви

The heart-stopping true story of how a group of recklessly brave students dug a tunnel under the Berlin Wall – and helped 29 mud-soaked men, women and children escape East Germany

Душераздирающая правдивая история о том, как группа безрассудно смелых студентов прорыла тоннель под Берлинской стеной и помогла 29 пропитанным грязью мужчинам, женщинам и детям бежать из Восточной Германии.

By Helena Merriman For The Mail On Sunday

Published: 17:31 EDT, 31 July 2021

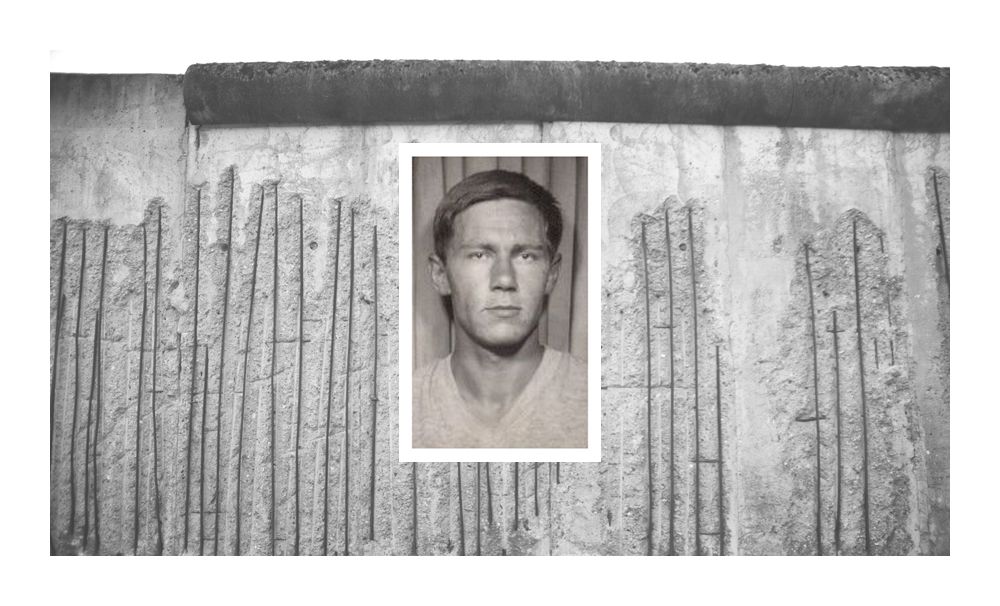

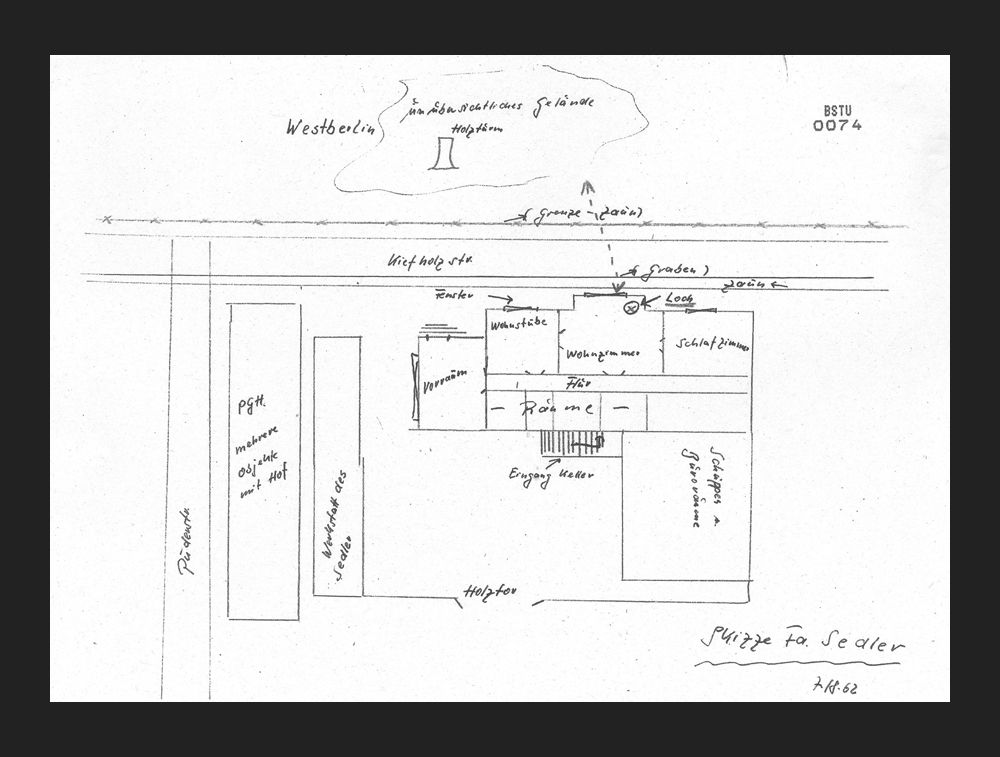

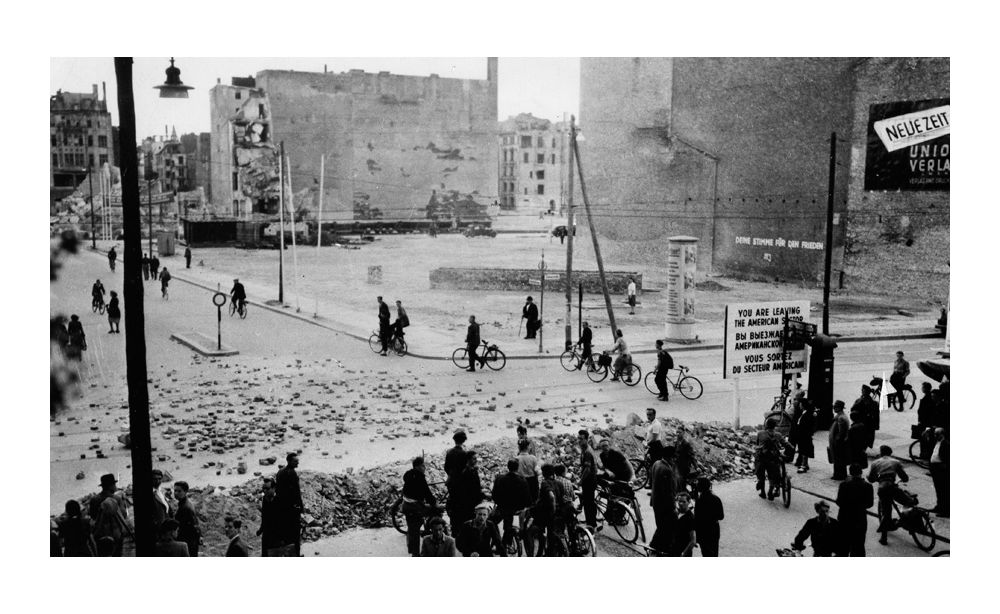

The gripping story of how, in 1962, a group of students dug a tunnel under the Berlin Wall to help 29 people escape East Germany was turned into a nerve-jangling BBC podcast. Now, drawing on interviews with those involved and countless pages of Stasi documents, the podcast’s creator has written a book telling the full, extraordinary tale of the bravery of those who risked everything for freedom. Engineering student Joachim Rudolph peers into the black hole in front of him. It’s a tunnel stretching 260ft from West to East Berlin. All he can see is darkness. Two companions, Hasso and Uli, crouch beside him. They are planning to lead 100 people from the Communist-controlled East under the Berlin Wall to freedom in the West. The opening of the tunnel in West Berlin is in a factory and the passage leads to a house in the East in a street called Puderstrasse, where, they hope, a group of men, women and children will be waiting to make the crawl to freedom. Each of the trio have their own reasons for helping the escapers. For months, they’ve been working in shifts, crawling and digging in the dark, always fearing that the passageway might cave in, burying them.

Захватывающая история о том, как в 1962 году группа студентов прорыла туннель под Берлинской стеной, чтобы помочь группе из 29 человек бежать из Восточной Германии, была превращена в увлекательный подкаст BBC. Теперь, опираясь на интервью с участниками и бесчисленные страницы документов Штази, создатель подкаста написал книгу, рассказывающую полную, необыкновенную историю о храбрости тех, кто рискнул всем ради свободы. Студент-инженер Иоахим Рудольф смотрит в черную дыру перед собой. Это туннель, протянувшийся на 260 футов от Западного до Восточного Берлина. Он видит только темноту. Два товарища, Хассо и Ули, приседают рядом с ним. Они планируют провести 100 человек с контролируемого коммунистами Востока под Берлинской стеной к свободе на Западе. Туннель в Западном Берлине открывается на заводе, а проход ведет к дому на Востоке на улице Пудерштрассе, где, как они надеются, группа мужчин, женщин и детей будет ждать, чтобы проползти к свободе. У каждого из троицы есть свои причины помогать провожатым. В течение нескольких месяцев они работали посменно, ползая и копая в темноте, постоянно опасаясь, что проход может обрушиться и похоронить их.

+7

+7

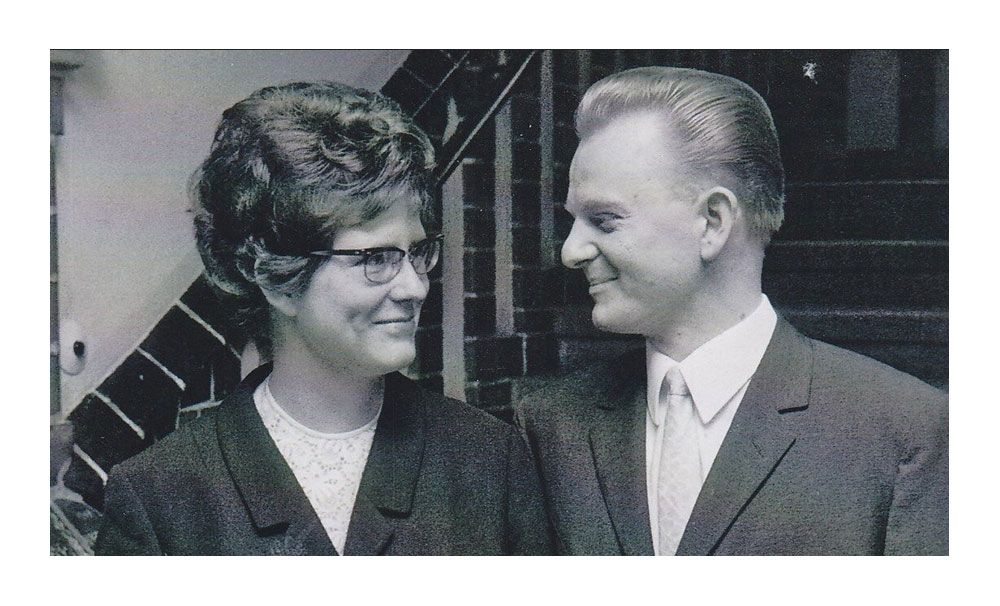

Caked in mud, Evi and Peter Schmidt comfort Annet. East German border guards (VoPos) were under orders to shoot all escapees / Эви и Петер Шмидт, покрытые грязью, утешают Аннет. Восточногерманские пограничники (VoPos) получили приказ расстреливать всех беглецов

The most dangerous part of the operation will be the final push: crawling along the tunnel and smashing up into the house. Самой опасной частью операции будет последний рывок: проползти по туннелю и проникнуть в дом.

Joachim and his friends have armed themselves with two pistols, an old machine-gun and a sawn-off shotgun. If they’re caught, they’re not going to be taken alive. Numerous people have been killed attempting to scale the Wall, which had been built to supplement the 900-mile barbed-wire fence running the length of East Germany. Initially the authorities let people travel between East and West Berlin for work, or to see family and friends, but after the Wall was built, mothers had become separated from their babies, brothers from sisters, friends and lovers separated and grandparents unable to see grandchildren. East German border guards (VoPos) were under orders to shoot all escapees. Gunter Litfin, a 24-year-old tailor, almost made it to the other side by swimming across the River Spree, but when he came up for air he was shot in the back of the head. Among those Joachim and his fellow diggers wanted to rescue were Peter and Evi Schmidt and their baby, Annet. Peter had worked as a graphic artist in West Berlin but lost his job when the Wall was built and he was not allowed to cross the border.

Иоахим и его друзья вооружились двумя пистолетами, старым пулеметом и обрезком ружья. Если их поймают, живыми их не возьмут. Многие люди погибли, пытаясь преодолеть Стену, которая была построена в дополнение к 900-мильному забору из колючей проволоки, протянувшемуся по всей территории Восточной Германии. Первоначально власти разрешали людям перемещаться между Восточным и Западным Берлином по работе или для того, чтобы увидеться с семьей и друзьями, но после строительства Стены матери стали разлучаться со своими детьми, братья с сестрами, друзья и любовники разлучались, а бабушки и дедушки не могли видеться с внуками. Восточногерманские пограничники (VoPos) получили приказ стрелять во всех беглецов. Гюнтер Литфин, 24-летний портной, почти добрался до другого берега, переплыв реку Шпрее, но когда он поднялся на воздух, его застрелили в затылок. Среди тех, кого хотели спасти Иоахим и его товарищи, были Петер и Эви Шмидт и их ребенок Аннет. Петер работал художником-графиком в Западном Берлине, но потерял работу, когда была построена стена, и ему не разрешили пересечь границу.

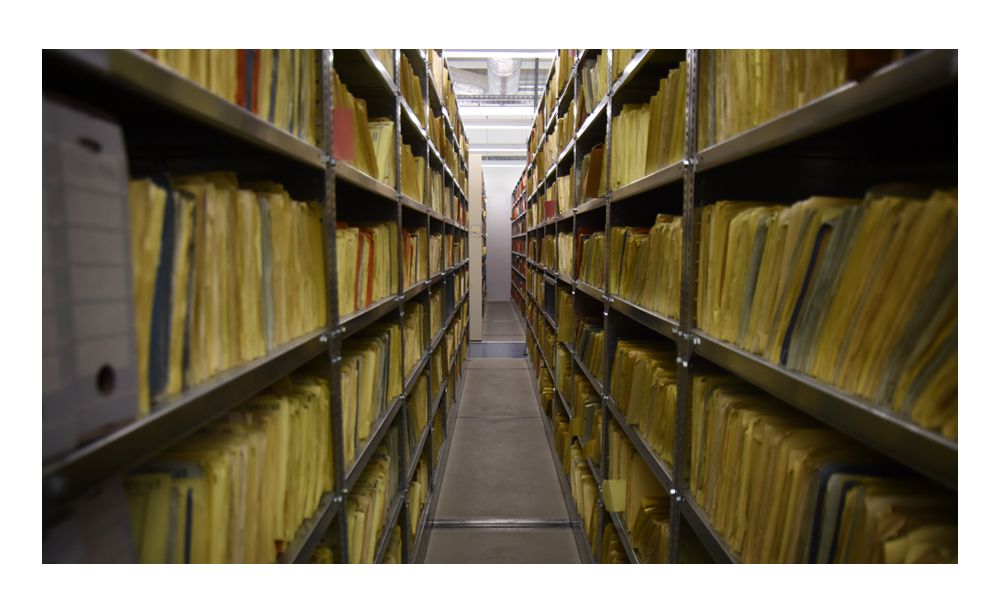

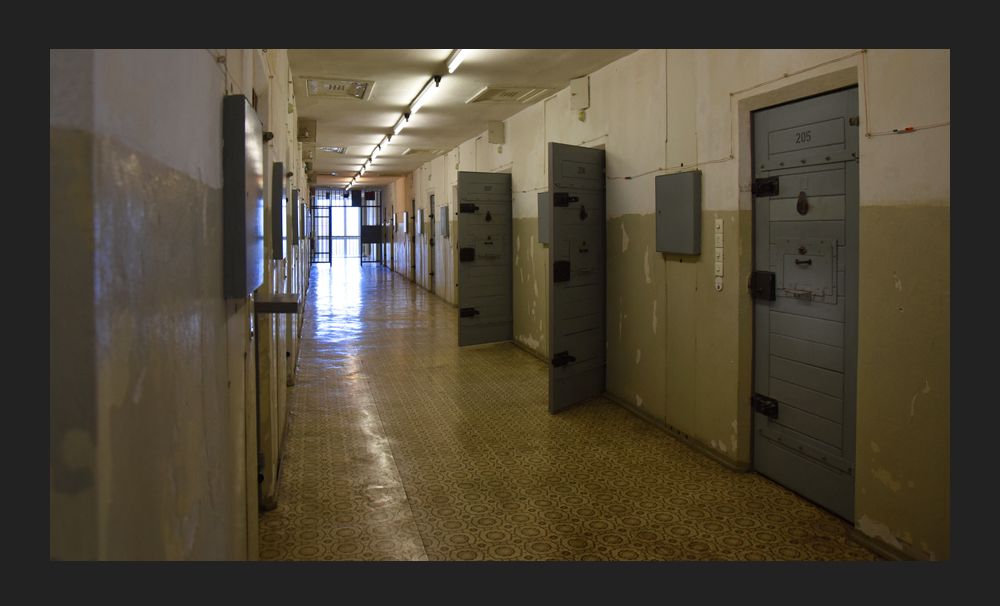

Friends of the Schmidts, Italian art students Mimmo Sesta and Gigi Spina, who were allowed to cross the border, often tried to convince the couple to escape but Peter always said no, it was too dangerous. After being called up to join the East German Army, Peter changed his mind. But how could they escape with the Stasi – East Germany’s feared secret police – so determined to stem the tide of escapes that every citizen was under surveillance from a network of spies monitoring the entire country? The Stasi wanted to know everything: where you worked, what you read, who you were married to, who you were sleeping with. They would break in to apartments and hide cameras and microphones in phones and light fittings to record every hour of people’s waking and sleeping life. Find enough dirt and they would take suspects to the Stasi HQ, known as The House Of One Thousand Eyes, for interrogation and psychological torture.

Друзья Шмидтов, итальянские студенты-художники Миммо Сеста и Джиджи Спина, которым было разрешено пересекать границу, часто пытались убедить супругов бежать, но Петер всегда отказывался, это было слишком опасно. После призыва в армию Восточной Германии Петер изменил свое решение. Но как они могли сбежать, когда Штази – тайная полиция Восточной Германии – была настолько решительно настроена остановить волну побегов, что каждый гражданин находился под наблюдением сети шпионов, следивших за всей страной? Штази хотели знать все: где вы работаете, что читаете, на ком женаты, с кем спите. Они входили в квартиры и прятали камеры и микрофоны в телефонах и светильниках, чтобы записывать каждый час бодрствования и сна людей. Если находили достаточно компромата, подозреваемых доставляли в штаб-квартиру Штази, известную как “Дом тысячи глаз”, для допросов и психологических пыток.

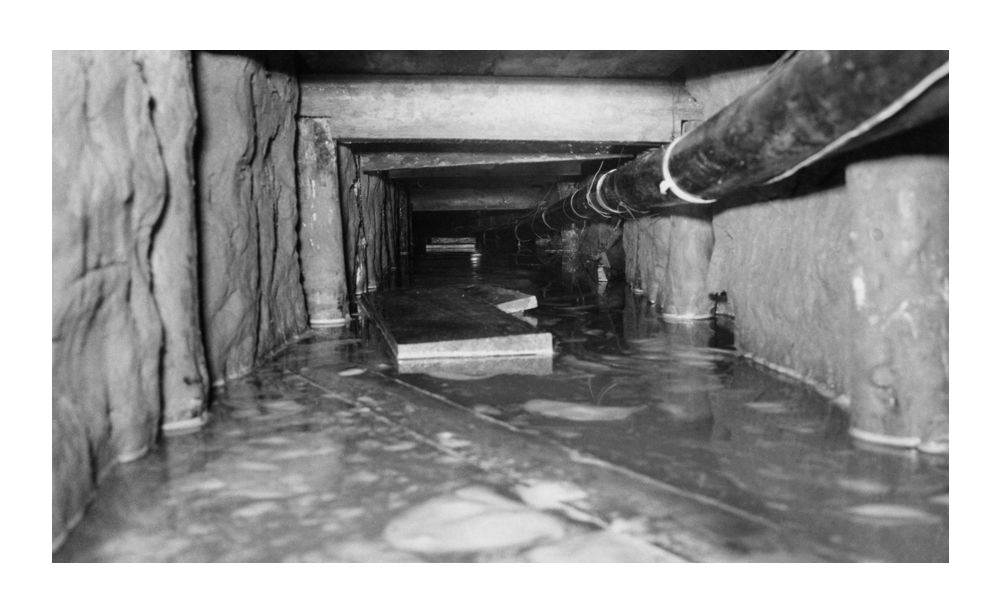

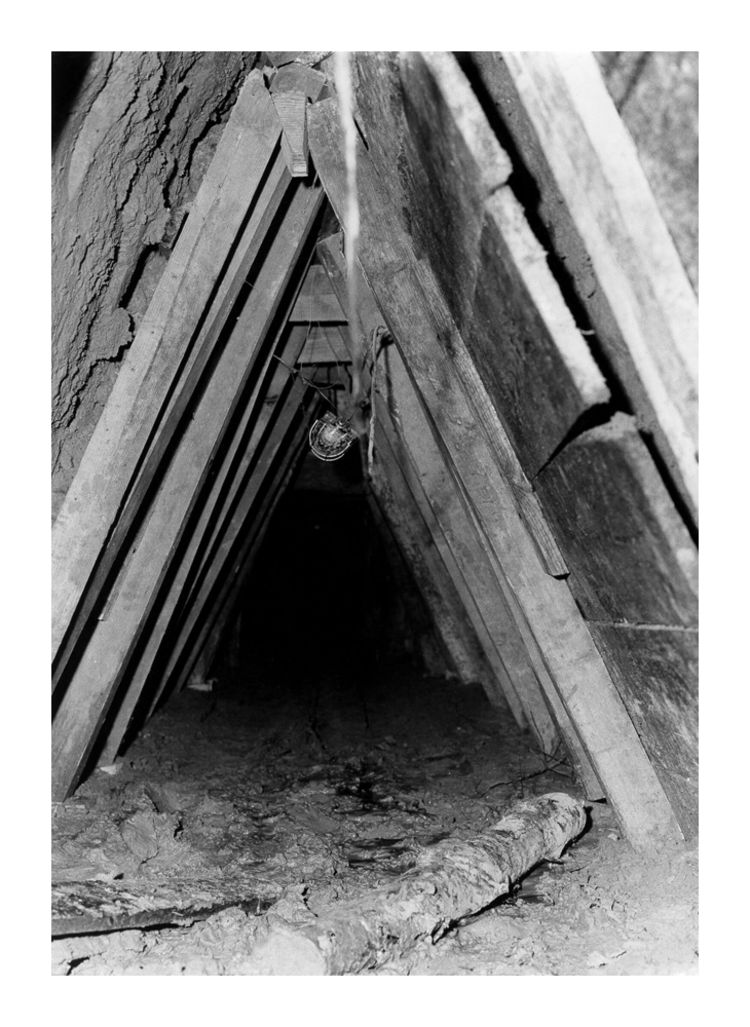

Flooded: Inside the original tunnel, which was later drained and repaired / Затоплен: Внутри первоначального туннеля, который позже был осушен и отремонтирован

Peter and Evi were unaware that two of their neighbours were Stasi informants who were reporting on their visitors from West Berlin. After discussing various options for their escape, Mimmo suggested they tried to escape via a tunnel and, in October 1961, he visited Joachim at his university dormitory in West Berlin to ask him to help dig. Joachim realised he risked being killed. Only recently, a fellow West Berliner had been shot while helping a woman escape through the barbed wire. He lay bleeding to death as West Berlin and British police watched helplessly, afraid to trespass. In any case, if they built a tunnel, what if it collapsed and Joachim was buried alive? Yet he agreed to help. How do you dig a tunnel into the world’s most heavily guarded country? How do you find somewhere safe to dig from and somewhere safe to dig to? First, the owner of a factory on the Western side of the Wall agreed to let them use his basement, hidden from the VoPos’ binoculars. So just before midnight on May 9, 1962, Mimmo, Gigi, Joachim and two others started digging. They dug for hours, until they were 13ft down. Then they started digging horizontally. After a few days, they had the beginnings of a tunnel. It was just 3ft by 3ft. They lay flat on their backs. They would have to dig like this for the length of a football pitch. Others joined them, including Hasso Herschel and engineer Uli Pfeifer.

Петер и Эви не знали, что двое из их соседей были осведомителями Штази, которые докладывали об их посетителях из Западного Берлина. После обсуждения различных вариантов побега Миммо предложил им попытаться сбежать через туннель, и в октябре 1961 года он посетил Йоахима в его университетском общежитии в Западном Берлине, чтобы попросить его помочь в рытье. Иоахим понял, что рискует быть убитым. Совсем недавно его товарищ из Западного Берлина был застрелен, когда помогал женщине пробраться через колючую проволоку. Он лежал, истекая кровью, а западноберлинская и британская полиция беспомощно наблюдала за ним, боясь нарушить границу. В любом случае, если они построят туннель, что если он обрушится и Йоахим будет погребен заживо? И все же он согласился помочь. Как прорыть туннель в самой охраняемой стране мира? Как найти безопасное место, откуда копать и куда копать? Сначала владелец фабрики на западной стороне Стены согласился разрешить им использовать его подвал, скрытый от биноклей ВоПо. Итак, незадолго до полуночи 9 мая 1962 года Миммо, Джиджи, Йоахим и еще двое начали копать. Они копали несколько часов, пока не опустились на 13 футов вниз. Затем они начали копать горизонтально. Через несколько дней у них появилось начало туннеля. Он был всего 3 на 3 фута. Они легли на спину. Им пришлось бы копать так на протяжении всего футбольного поля. К ним присоединились другие, в том числе Хассо Гершель и инженер Ули Пфайфер.

Hasso wanted to rescue his sister Anita and her family. Uli had escaped from the East through a sewer but his girlfriend had been caught and sentenced to seven years in prison. He wanted revenge against East Germany. They worked in shifts. After eight hours they were exhausted, arms shaking, eyelashes clumped with mud, hands blistered. With their engineering ingenuity they installed breathing pipes, lighting and even telephones. But after two months of digging, disaster: a leak. The tunnel was filling with water. The escape couldn’t go ahead. Then they learned about another tunnel – abandoned and unfinished. In order to ensure it was heading in the right direction, one tunneller crawled ahead and stuck a rod through the ceiling and into the air above so a colleague with binoculars could see where it came out. They decided to continue digging in this one. The escape was planned for August 7, almost a year after the Wall was built. Crucially, they needed someone to make contact with the escapees in East Berlin to tell them when to be ready. Siegfried Uhse, a 21-year-old hairdresser, volunteered. However, they didn’t realise he was a Stasi informant. Caught smuggling cigarettes and alcohol into East Berlin, Siegfried had been interrogated by the Stasi, who learned that he was homosexual – an imprisonable offence. Faced with the choice of jail or becoming an informant, Siegfried made his decision. He reported everything to his Stasi handler. And so, when Joachim surfaced from the tunnel in the house in the East on Puderstrasse, the Stasi were waiting, positioned outside the window. When Hasso and Uli climbed out, too, they had no clue the Stasi were ready to pounce, with East German soldiers inside the house, watching through a crack in the living-room door.

Хассо хотел спасти свою сестру Аниту и ее семью. Ули сбежал с Востока через канализацию, но его девушку поймали и приговорили к семи годам тюрьмы. Он хотел отомстить Восточной Германии. Они работали посменно. Через восемь часов они были измотаны, руки тряслись, ресницы слиплись от грязи, руки покрылись волдырями. Благодаря своей инженерной смекалке они установили дыхательные трубы, освещение и даже телефоны. Но после двух месяцев копания произошла катастрофа: утечка. Туннель заполнялся водой. Побег не мог продолжаться. Тогда они узнали о другом туннеле – заброшенном и недостроенном. Чтобы убедиться, что он идет в правильном направлении, один из проходчиков пролез вперед и просунул прут сквозь потолок и в воздух, чтобы коллега с биноклем мог видеть, где он выходит. Они решили продолжить копать в этой шахте. Побег был запланирован на 7 августа, почти через год после возведения Стены. Очень важно, что им нужен был кто-то, кто мог бы связаться с беглецами в Восточном Берлине и сообщить им о готовности. Добровольцем вызвался Зигфрид Узе, 21-летний парикмахер. Однако они не знали, что он был осведомителем Штази. Пойманный на контрабанде сигарет и алкоголя в Восточный Берлин, Зигфрид был допрошен сотрудниками Штази, которые узнали, что он гомосексуалист – преступление, за которое полагается тюремное заключение. Оказавшись перед выбором: тюрьма или стать информатором, Зигфрид принял решение. Он доложил обо всем своему куратору из Штази. И вот, когда Иоахим вынырнул из туннеля в доме на востоке на Пудерштрассе, Штази уже ждали, расположившись за окном. Когда Хассо и Ули тоже вылезли наружу, они не знали, что Штази были готовы к нападению, а в доме находились восточногерманские солдаты, наблюдавшие за ними через щель в двери гостиной.

Just as the soldiers were about to burst in, they heard one of the diggers say: ‘My pistol isn’t working. Pass me the machine-gun.’ The Stasi guards paused. Their old Soviet Kalashnikovs were no match for Western machine-guns. However, if they waited for back-up, the diggers might get away. Suddenly, the diggers’ walkie-talkie crackled. ‘Come back now! It’s over!’ their friends’ voices could be heard, shouting from their vantage point in West Berlin where they could see the Stasi and soldiers. The three tunnellers jumped down into the hole, crawling frantically back to West Berlin, dreading the moment when the Stasi would face them and open fire. They scrabbled as fast as they could in the tiny, dark space: crawling, crawling until eventually they reached daylight. Minutes later, the soldiers’ reinforcements arrived. They were too late. The tunnel was empty. But thanks to informant Siegfried, they managed to round up 43 would-be escapees as they arrived in Puderstrasse, bundled them into cars and vans and took them off for interrogation. Their greatest catch was Wolfdieter Sternheimer. He was a student who had been tasked with giving the escapees – including his girlfriend Renate – details of when to get to the house. That achieved, he’d then headed for a border crossing, tingling with excitement at the thought of seeing Renate.

Когда солдаты уже собирались ворваться внутрь, они услышали, как один из землекопов сказал: “Мой пистолет не работает. Передайте мне пулемет”. Охранники Штази приостановились. Их старые советские автоматы Калашникова не шли ни в какое сравнение с западными пулеметами. Однако, если они будут ждать подкрепления, землекопы могут уйти. Внезапно рация землекопов затрещала. ‘Возвращайтесь! Все кончено!” – послышались голоса их друзей, кричавших со своей точки обзора в Западном Берлине, откуда они могли видеть Штази и солдат. Трое тоннельщиков спрыгнули в дыру и бешено поползли обратно в Западный Берлин, боясь того момента, когда Штази столкнется с ними и откроет огонь. Они пробирались в крошечном темном пространстве так быстро, как только могли: ползли, ползли, пока в конце концов не добрались до дневного света. Через несколько минут прибыло подкрепление солдат. Они опоздали. Туннель был пуст. Но благодаря осведомителю Зигфриду им удалось собрать 43 потенциальных беглеца, которые прибыли на Пудерштрассе, погрузить их в машины и фургоны и отвезти на допрос. Самой большой добычей стал Вольфдитер Штернхаймер. Он был студентом, которому было поручено сообщить беглецам – в том числе его подруге Ренате – информацию о том, когда нужно добраться до дома. Получив это, он направился к пограничному пункту, испытывая волнение при мысли о встрече с Ренатой.

At the checkpoint, Wolfdieter gave his papers to two men in uniform. ‘Come with us,’ the VoPos said as they put him in a car. His knees started to shake. Fifteen minutes later he arrived at the East Berlin police HQ and was handed to the Stasi. After relentless interrogation and psychological torture, Wolfdieter was sentenced to seven years in prison. He’d be 29 when he was out. But what about his girlfriend, Renate? A few weeks later he was taken back to court. To his dismay, she was in the dock. Renate had managed to get away from the Stasi during the aborted tunnel escape – along with Peter and Evi Schmidt – but someone gave her name to the secret police. With chilling vindictiveness, the Stasi had brought Wolfdieter to court to watch Renate being sentenced. She got three years. As the guards led Renate away, she put out her hand. Wolfdieter put out his, and for a few seconds their fingers curled together, before their hands were ripped apart and Renate disappeared. Meanwhile, Wolfdieter had worked out that it was Siegfried Uhse who had betrayed them. But, now jailed, he had no means of telling the rest of the group.

На контрольно-пропускном пункте Вольфдитер отдал свои документы двум мужчинам в форме. Пойдемте с нами”, – сказали вопосы, усаживая его в машину. Его колени начали дрожать. Через пятнадцать минут он прибыл в штаб-квартиру полиции Восточного Берлина и был передан сотрудникам Штази. После неустанных допросов и психологических пыток Вольфдитера приговорили к семи годам тюрьмы. Когда он вышел на свободу, ему было бы 29 лет. А как же его девушка Рената? Через несколько недель его снова доставили в суд. К его ужасу, она была на скамье подсудимых. Ренате удалось скрыться от Штази во время неудачного побега из тоннеля – вместе с Петером и Эви Шмидт – но кто-то сообщил ее имя тайной полиции. С леденящей душу мстительностью Штази привела Вольфдитера в суд, чтобы он посмотрел, как Ренате вынесут приговор. Она получила три года. Когда охранники выводили Ренату, она протянула руку. Вольфдитер протянул свою, и на несколько секунд их пальцы сплелись, а затем их руки разорвали, и Рената исчезла. Тем временем Вольфдитер выяснил, что это Зигфрид Узе предал их. Но теперь, в тюрьме, у него не было возможности рассказать об этом остальным членам группы.

How do you dig a tunnel into the world’s most heavily guarded country? How do you find somewhere safe to dig from and somewhere safe to dig to? / Как прорыть туннель в самой охраняемой стране мира? Как найти безопасное место, откуда можно копать, и безопасное место, куда можно копать?

+7

+7

The owner of a factory on the Western side of the Wall agreed to let them use his basement, hidden from the VoPos’ binoculars / Владелец фабрики на западной стороне Стены согласился разрешить им использовать свой подвал, скрытый от биноклей ВоПо.

Just before midnight on May 9, 1962, Mimmo, Gigi, Joachim and two others started digging. They dug for hours, until they were 13ft down. Then they started digging horizontally / Незадолго до полуночи 9 мая 1962 года Миммо, Джиджи, Йоахим и еще двое начали копать. Они копали несколько часов, пока не оказались на глубине 13 футов. Затем они начали копать горизонтально

After a few days, they had the beginnings of a tunnel. It was just 3ft by 3ft. They lay flat on their backs. They would have to dig like this for the length of a football pitch. Others joined them, including Hasso Herschel and engineer Uli Pfeifer / Через несколько дней у них появилось начало туннеля. Он был всего 3 на 3 фута. Они легли на спину. Им пришлось бы копать так на протяжении всего футбольного поля. К ним присоединились другие, в том числе Хассо Гершель и инженер Ули Пфайфер.

That meant that when Joachim and the others decided to return to the original tunnel to try again – the leak having been fixed – Siegfried duly informed his Stasi handler, although he didn’t know the exact location of this tunnel. The diggers feared they didn’t have long before the tunnel might collapse. They would either have to abandon it or quickly start digging upwards and emerge in an alternative cellar, in Schonholzer Strasse. This would be much nearer the Wall, closer to VoPos patrols and therefore much more risky and dangerous. In the meantime, Mimmo and Gigi used their Italian nationality to legally cross the border on September 9 to tell their friends Evi and Peter of the new escape plan: ‘Get ready to leave in five days.’ With Wolfdieter in prison, another messenger was needed to alert the other escapees. But who would risk arrest, or death? Mimmo’s girlfriend Ellen, who had a West German passport, agreed to do it, even though she had never been to East Berlin. Mimmo gave her a map and identified three pubs. In each, he told her, a handful of escapees would be waiting. Mostly families with young children. When Ellen walked in, she would give a coded signal that the tunnel was ready. Ellen memorised the map and Mimmo’s instructions. On the morning of September 14, Ellen covered her striking red hair in a cream headscarf. Her stomach churning, she boarded a train for East Berlin while being filmed by a TV crew from the American broadcaster NBC, which had helped fund the tunnel in exchange for filming the escape at the West Berlin end.

Это означало, что когда Иоахим и другие решили вернуться к первоначальному туннелю, чтобы попытаться пройти его снова – утечка была устранена – Зигфрид должным образом сообщил об этом своему куратору из Штази, хотя он и не знал точного местоположения этого туннеля. Копатели опасались, что до обрушения туннеля осталось недолго. Им пришлось бы либо покинуть его, либо быстро начать копать вверх и выйти в альтернативном подвале на Шонхольцерштрассе. Это было бы гораздо ближе к Стене, ближе к патрулям VoPos и, следовательно, гораздо рискованнее и опаснее. Тем временем Миммо и Джиджи использовали свое итальянское гражданство, чтобы легально пересечь границу 9 сентября и рассказать своим друзьям Эви и Петеру о новом плане побега: ‘Приготовьтесь уехать через пять дней’. Поскольку Вольфдитер находился в тюрьме, нужен был еще один гонец, чтобы оповестить других беглецов. Но кто мог рискнуть арестом или смертью? Подруга Миммо Эллен, у которой был западногерманский паспорт, согласилась сделать это, хотя она никогда не была в Восточном Берлине. Миммо дал ей карту и указал три паба. В каждом из них, сказал он ей, будет ждать горстка беглецов. В основном семьи с маленькими детьми. Когда Эллен войдет, она подаст кодированный сигнал, что туннель готов. Эллен запомнила карту и инструкции Миммо. Утром 14 сентября Эллен закрыла свои потрясающие рыжие волосы кремовой косынкой. Схватившись за живот, она села на поезд в Восточный Берлин, а в это время ее снимала съемочная группа американской телекомпании NBC, которая помогала финансировать строительство туннеля в обмен на съемку побега из Западного Берлина.

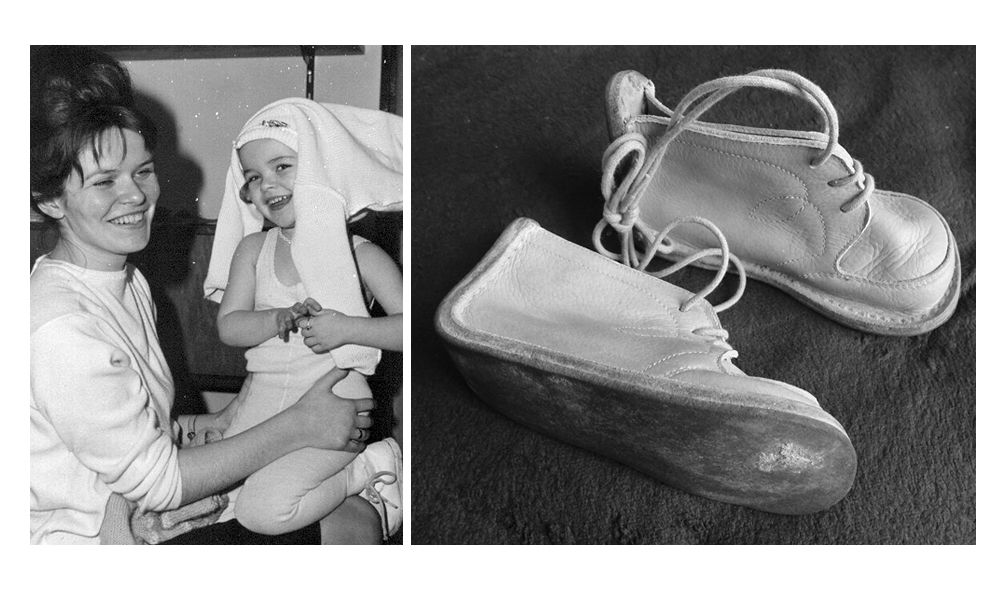

Beaming Evi and Annet (6) clean up after their escape / Радостные Эви и Аннет (6 лет) отмываются после побега

In East Berlin, Evi Schmidt got ready to leave her home for ever. She and husband Peter had managed to evade the Stasi during the previous escape attempt, but others who’d been caught were now in prison. If it went wrong, Evi could lose her own little daughter, Annet. A new digger had joined the team: Claus, a butcher, who told the others that he’d escaped from East Berlin months earlier but that his pregnant wife, Inge, had been caught with their toddler, Kirsten. Kirsten had been put in a children’s home and Inge sent to prison but released in time to give birth to their son, Uwe, whom Claus had never met. He offered to help dig if Inge and their children could be included in the escape. The others were suspicious – they still didn’t know who had betrayed them last time. But they needed another digger and his story checked out. In the tunnel, Hasso and Joachim started crawling. The wet clay squelched under them as they scrabbled under the Wall and into East Berlin. At the end they stood up and looked at the ceiling. Hasso climbed on to Joachim’s shoulders and drilled through the brick, then smashed it until the hole was big enough to climb through. They squeezed into the cellar. The water in the tunnel was rising. They didn’t have much time. After checking that they had the right house, Number 7, Joachim phoned the escapees: they were in the right place. The messages bounced from phone to walkie-talkie to phone, eventually reaching the NBC cameraman in a building in West Berlin, high above the Wall. He flung a white sheet out of the window. On the other side of the Wall, Ellen saw this signal. They were ready. She set off to alert the escapers. Striding to a bar, she loudly asked for some matches. This was the signal, and she hoped the escapees had noticed it. They had. Others quickly followed.

В Восточном Берлине Эви Шмидт готовилась навсегда покинуть свой дом. Во время предыдущей попытки побега ей и мужу Петеру удалось ускользнуть от Штази, но другие, пойманные, теперь сидели в тюрьме. Если бы все пошло не так, Эви могла бы потерять собственную маленькую дочь Аннет. К команде присоединился новый диггер: Клаус, мясник, который рассказал остальным, что он сбежал из Восточного Берлина несколькими месяцами ранее, но его беременная жена Инге была поймана вместе с их малышкой Кирстен. Кирстен поместили в детский дом, а Ингу отправили в тюрьму, но выпустили вовремя, чтобы она успела родить их сына Уве, которого Клаус никогда не видел. Он предложил помощь в раскопках, если Инге и их дети будут участвовать в побеге. Остальные отнеслись к этому с подозрением – они все еще не знали, кто предал их в прошлый раз. Но им нужен был еще один землекоп, и его история подтвердилась. В туннеле Хассо и Иоахим начали ползти. Мокрая глина хлюпала под ними, когда они пробирались под стеной в Восточный Берлин. В конце они встали и посмотрели на потолок. Хассо взобрался на плечи Йоахима и просверлил кирпич, а затем разбил его, пока дыра не стала достаточно большой, чтобы пролезть. Они протиснулись в подвал. Вода в туннеле поднималась. У них было мало времени. Убедившись, что они нашли нужный дом, номер 7, Иоахим позвонил беглецам: они были в нужном месте. Сообщения переходили от телефона к рации, от рации к телефону и в конце концов дошли до оператора NBC в здании в Западном Берлине, высоко над стеной. Он выбросил из окна белую простыню. По ту сторону стены Эллен увидела этот сигнал. Они были готовы. Она отправилась оповестить провожающих. Подойдя к бару, она громко попросила спички. Это был сигнал, и она надеялась, что беглецы его заметили. Они заметили. Другие быстро последовали за ней.

Ellen’s work was done. She had to get out of East Berlin, fast. But at the railway station, a policewoman stopped her. She was taken to a small room and stripped naked. The policewoman searched her but found nothing and let her go. Terrified and humiliated, Ellen ran on to the train. Moments later she heard with relief: ‘You are now leaving East Berlin.’ At 6pm, Peter and Evi arrived at the house on Schonholzer Strasse and were led down into the tunnel. A digger took little Annet from Evi. Evi started crawling through the darkness. Joachim watched. He had to stay there, in the East, until everyone had crawled through. A steady stream of escapees had arrived, including Hasso’s sister, Anita, with her husband and toddler. At the other end, in the West, the NBC crew were waiting at the top of the shaft that led into the tunnel, camera pointing at the hole. It was dark. Nothing moved. Then a white handbag appeared. Then a hand. An arm. A woman crawled out of the tunnel, covered in mud. It had taken Evi 12 minutes to crawl through the dirt and water. As she reached the top of the ladder, she fainted and one of the TV crew caught her. Moments later, Mimmo appeared, holding Annet. She had lost her tiny shoes in the tunnel. Evi bundled her child into her arms, rocking her back and forth. The NBC crew filmed everyone as they crawled out of the tunnel: eight-year-olds, 18-year-olds, 80-year-olds. Each emerged wetter than the last – the water was now halfway up the tunnel. Claus was the only digger still waiting for someone. He was losing hope that his wife Inge would come. At 11pm, a hand emerged from the tunnel, then a woman covered in mud. Claus didn’t recognise her.

Работа Эллен была закончена. Ей нужно было поскорее уехать из Восточного Берлина. Но на вокзале ее остановила женщина-полицейский. Ее отвели в маленькую комнату и раздели догола. Полицейская обыскала ее, но ничего не нашла и отпустила. Испуганная и униженная, Эллен побежала на поезд. Через несколько минут она с облегчением услышала: “Вы покидаете Восточный Берлин”. В 6 часов вечера Петер и Эви подъехали к дому на Шонхольцерштрассе и спустились в туннель. Землекоп забрал у Эви маленькую Аннет. Эви начала ползти в темноте. Иоахим наблюдал. Он должен был оставаться там, на востоке, пока все не проползут. Постоянно прибывал поток беглецов, в том числе сестра Хассо, Анита, с мужем и малышом. На другом конце, на западе, съемочная группа NBC ждала на вершине шахты, ведущей в туннель, направив камеру на отверстие. Было темно. Ничего не двигалось. Затем появилась белая сумка. Потом рука. Рука. Из туннеля выползла женщина, вся в грязи. Эви понадобилось 12 минут, чтобы проползти через грязь и воду. Когда она достигла вершины лестницы, она потеряла сознание, и один из телевизионщиков поймал ее. Мгновением позже появился Миммо, держа на руках Аннет. Она потеряла в туннеле свои крошечные туфельки. Эви взяла ребенка на руки, покачивая ее вперед-назад. Съемочная группа NBC снимала всех, кто выползал из туннеля: восьмилетних, 18-летних, 80-летних. Каждый выходил из тоннеля более мокрым, чем предыдущий – вода поднялась уже на половину тоннеля. Клаус был единственным землекопом, который все еще кого-то ждал. Он уже терял надежду, что его жена Инге придет. В 11 часов вечера из туннеля показалась рука, затем женщина, покрытая грязью. Клаус не узнал ее.

A digger next appeared, something white in his arms: a tiny baby just four months old. Claus knew, somehow, instinctively, that the child was his. As he cradled his child, Inge, too, realised that this mud-covered man was her husband. Claus and Inge moved towards each other. Joachim had counted 29 people into the tunnel. It was time for him to follow. The tunnel’s sides were beginning to fall in. He found a pair of children’s shoes as he crawled along and picked them up. His mind raced with memories of the past four months. The leaks. The mud. The blisters. The people who escaped. Knowing they were all safe in West Berlin, he felt intense happiness. Despite his efforts, Stasi informant Siegfried had been unable to discover the location of the tunnel. Four days later, the story of 29 East Berliners fleeing through a 400ft tunnel was splashed on the front pages of newspapers across the Western world. The Stasi were humiliated. On December 10, 1962, the NBC film – The Tunnel – was broadcast. The escapes continued, despite the Stasi’s efforts. Hasso and Uli dug other tunnels. Wolfdieter was released from prison after two years and married Renate. Evi and Peter’s marriage broke down, but she never forgot the man who helped her escape, Joachim Rudolph. Ten years later, they married. Joachim still has the shoes that Annet – now his stepdaughter – lost in the tunnel. At least 140 people were killed at the Berlin Wall before it was pulled down in November 1989. Even now, elsewhere, more walls are being built, dividing cities and countries. As Joachim says: ‘Wherever there’s a wall, people will try to get over it. Or under it.’

Следом появился землекоп с чем-то белым на руках: крошечный ребенок четырех месяцев от роду. Клаус каким-то образом, инстинктивно, понял, что это его ребенок. Когда он прижимал к себе ребенка, Инге тоже поняла, что этот покрытый грязью мужчина – ее муж. Клаус и Инга двинулись навстречу друг другу. Иоахим насчитал в туннеле 29 человек. Настало время и ему последовать за ними. Бока туннеля начали осыпаться. Ползком он нашел пару детских ботинок и поднял их. В его голове пронеслись воспоминания о последних четырех месяцах. Протечки. Грязь. Волдыри. Люди, которые сбежали. Зная, что все они находятся в безопасности в Западном Берлине, он испытывал сильное счастье. Несмотря на все свои усилия, информатор Штази Зигфрид не смог обнаружить местонахождение туннеля. Четыре дня спустя история о 29 жителях Восточного Берлина, бежавших через 400-футовый туннель, попала на первые полосы газет всего западного мира. Штази были унижены. 10 декабря 1962 года по каналу NBC был показан фильм “Туннель”. Побеги продолжались, несмотря на все усилия Штази. Хассо и Ули прорыли другие туннели. Вольфдитер был освобожден из тюрьмы через два года и женился на Ренате. Брак Эви и Петера распался, но она никогда не забывала человека, который помог ей бежать, Иоахима Рудольфа. Через десять лет они поженились. У Иоахима до сих пор хранятся туфли, которые Аннет – теперь уже его падчерица – потеряла в туннеле. По меньшей мере 140 человек были убиты у Берлинской стены, прежде чем она была снесена в ноябре 1989 года. Даже сейчас в других местах строятся новые стены, разделяющие города и страны. Как говорит Иоахим: “Где бы ни была стена, люди будут пытаться перебраться через нее. Или под ней”.

© Hugely Ltd and BBC, 2021

The story of Tunnel 29 (bbc.co.uk)

In 1961, Joachim Rudolph escaped from one of the world’s most brutal dictatorships. A few months later, he began tunnelling his way back in. Why?

The Tunnel / Туннель

It all began with a knock at the door. Joachim, a 22-year-old engineering student, was in his room at university in West Berlin. He had been studying there for a few months, spending his free time taking photographs, or going to jazz nights. At his door were two Italian students he knew in passing who had come to ask for his help. They needed to get some friends out of East Berlin and they wanted to do this by digging a tunnel. This was October 1961, just two months after the Berlin Wall had gone up. It was built by the East German government to stop the flood of people leaving the communist dictatorship for a better life in the West. But what was so extraordinary about it was the speed with which it had been built.

Все началось со стука в дверь. Иоахим, 22-летний студент-инженер, находился в своей комнате в университете в Западном Берлине. Он учился там уже несколько месяцев, в свободное время занимался фотографией или ходил на джазовые вечера. У его двери стояли два итальянских студента, которых он знал мимоходом и которые пришли попросить его о помощи. Им нужно было вывезти друзей из Восточного Берлина, и они хотели сделать это, прокопав туннель. Это было в октябре 1961 года, всего через два месяца после возведения Берлинской стены. Она была построена правительством Восточной Германии, чтобы остановить поток людей, покидающих коммунистическую диктатуру в поисках лучшей жизни на Западе. Но что было в ней необычного, так это скорость, с которой она была построена.

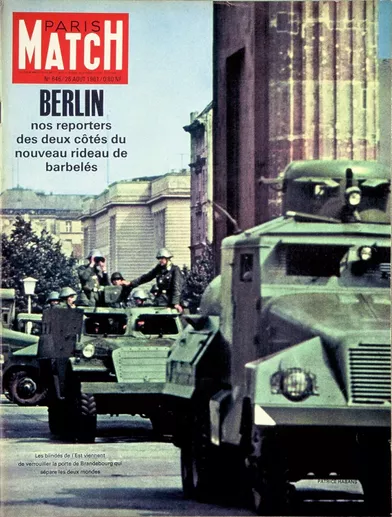

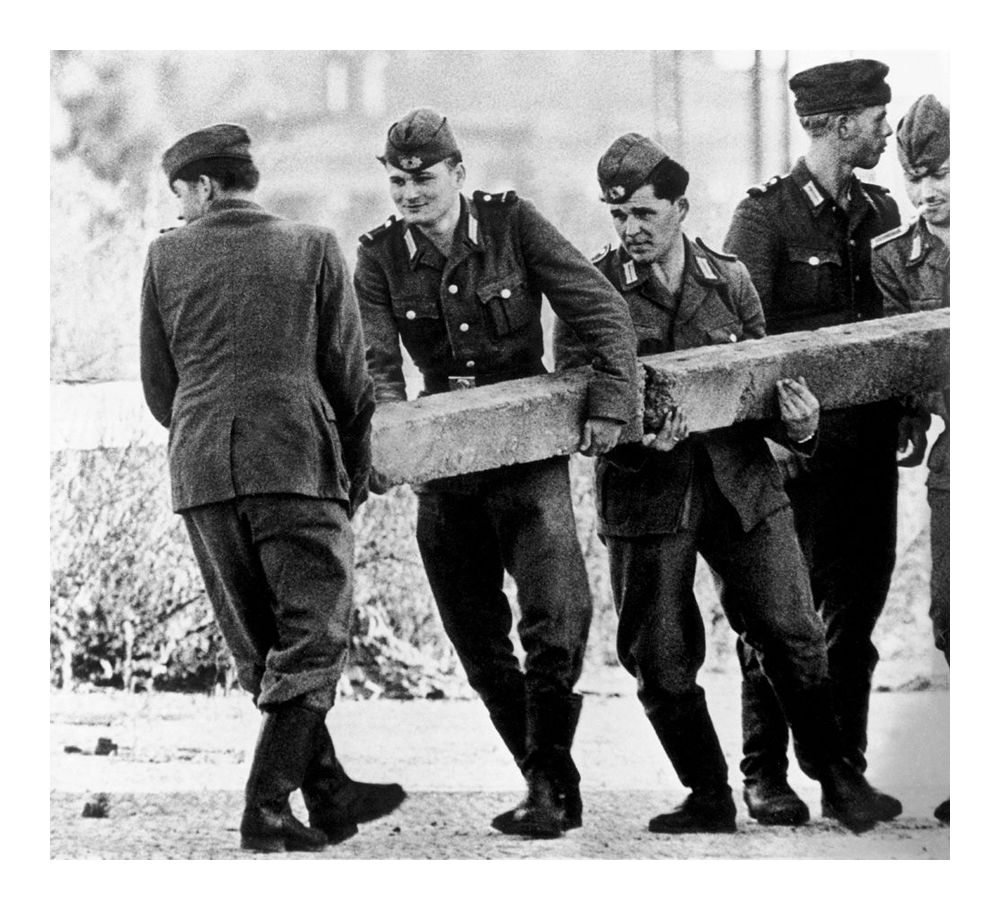

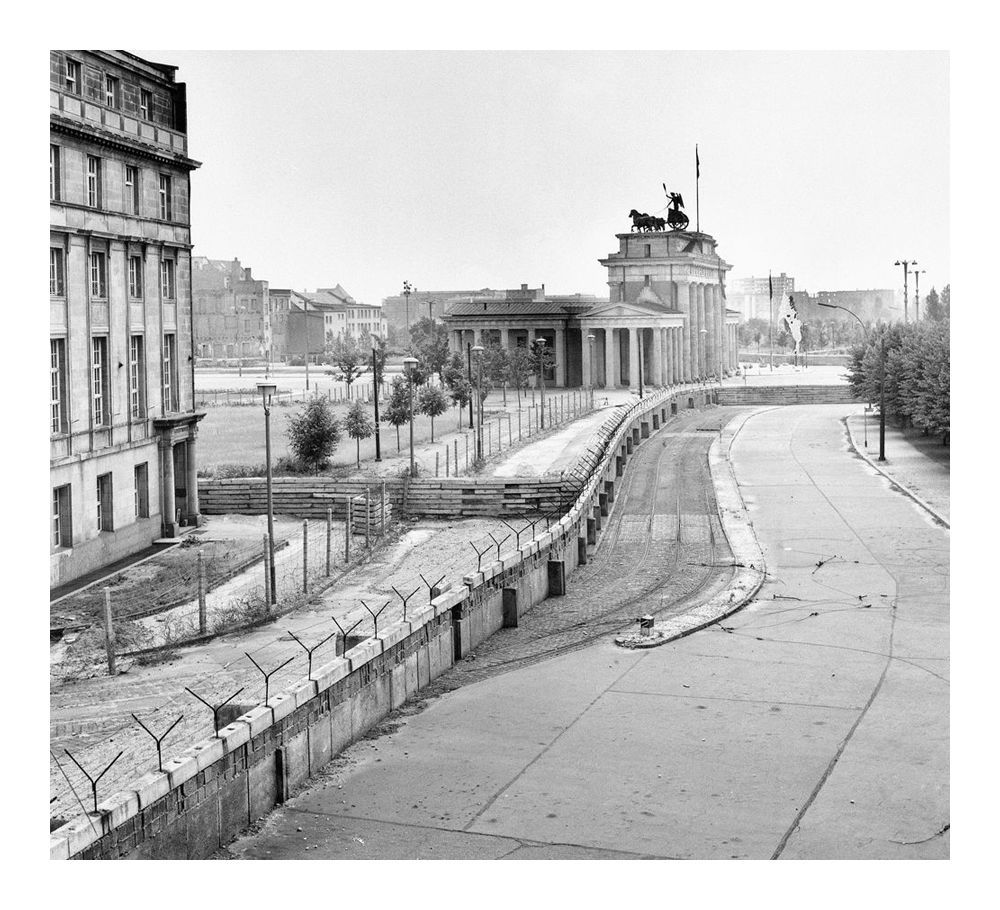

Tens of thousands of East German soldiers had gone into the streets of East Berlin in the dead of night, stringing barbed wire from posts and making concrete barricades. By the next morning, this barrier cut through the whole city, snaking through parks, playgrounds, cemeteries and squares. Although the wall had been hastily put together (and wasn’t as tall or as heavily guarded as it would later become) it changed the city overnight. When people woke up on 13 August 1961, they suddenly found themselves on one side of it. Wives were cut off from their husbands, brothers from their sisters. There were even stories of newborn babies in the West now separated from their mothers.

Десятки тысяч восточногерманских солдат вышли на улицы Восточного Берлина глубокой ночью, натягивая колючую проволоку на столбы и делая бетонные баррикады. К следующему утру этот барьер пересекал весь город, пробираясь через парки, детские площадки, кладбища и площади. Хотя стена была построена наспех (и была не такой высокой и не такой охраняемой, как впоследствии), она в одночасье изменила город. Проснувшись 13 августа 1961 года, люди вдруг обнаружили, что находятся по одну сторону стены. Жены были отрезаны от своих мужей, братья от своих сестер. Были даже рассказы о новорожденных младенцах на Западе, разлученных со своими матерями.

Life before the wall had been tough enough – people were fed up with the poor living conditions and the Soviet tanks that showed up every time protesters went out onto the streets. But now, with the wall, the government was displaying its desire for even greater control.

And so the very day the barrier was erected, the escapes began. Some people just jumped over the barbed wire, others were more inventive, like the couple who swam across the River Spree pushing their three-year-old daughter in front of them in a bathtub.

Even East German soldiers and border guards were among those trying to get out.

Then there were the people who sneaked into houses next to the wall, and threw themselves out of the windows, hoping that firemen on the other side would catch them.

Joachim himself had crawled through a field in the middle of the night, making it into the West just as the sun rose. “I didn’t want to be part of this new world,” he says now. “A world where you couldn’t say or think what you want.”

Now he was in West Berlin, making a new life for himself. But here were these two students, asking him to tunnel back into the country he’d only just escaped from. He could be thrown in prison, even killed.

Despite this, he found himself agreeing to help them.

Digging begins

When you’re a group of students, who have never dug a tunnel before, where do you begin? Like every good heist, they started with maps.

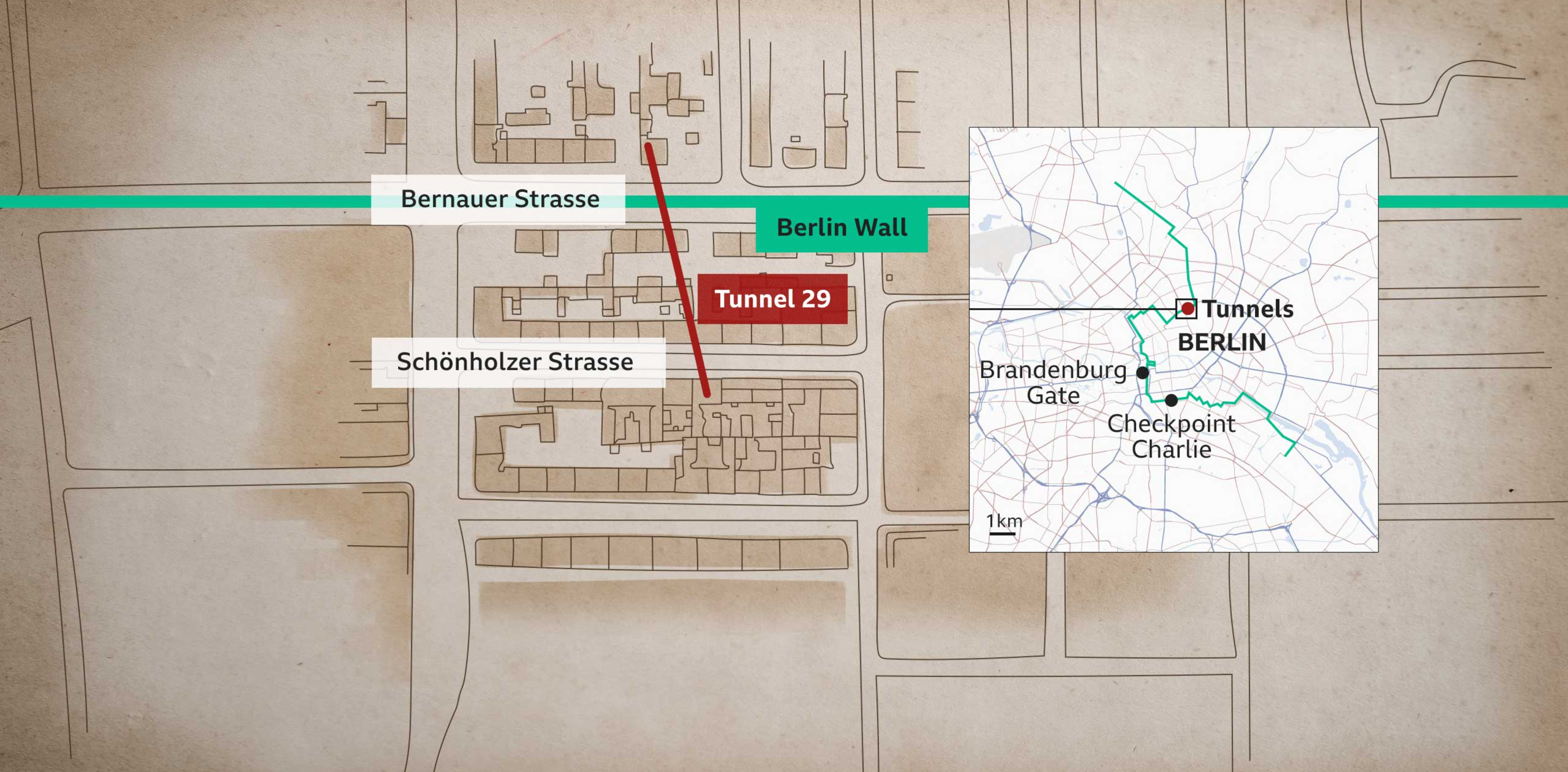

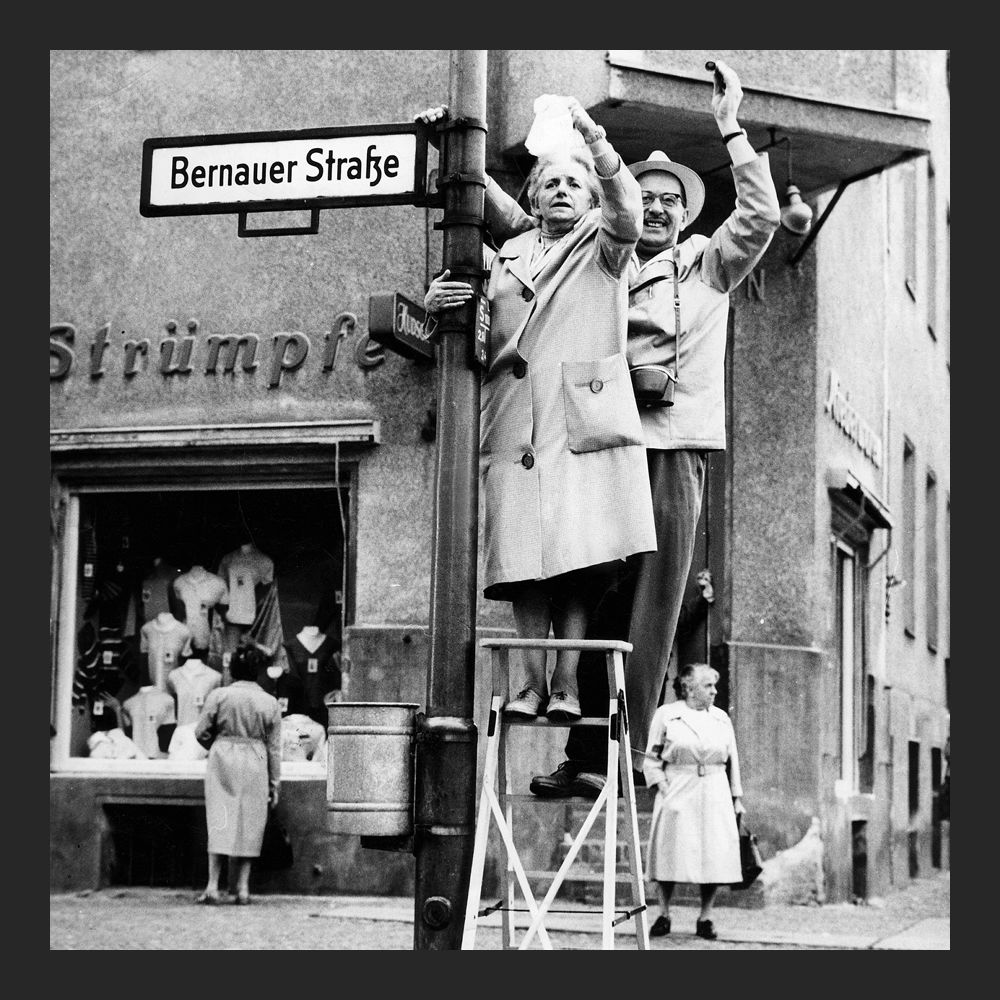

They borrowed them from friends in the government, and pored over them, trying to plot a route for the tunnel. They needed to find a street to burrow under, where they wouldn’t dig into the city’s water table. They chose Bernauer Strasse, which was a bold move.

Back in the 60s, this street was world-famous because the Berlin Wall ran right down the middle of it. Tourists would go there to take photos of the wall, so it was always busy. Choosing to dig under Bernauer Strasse was like digging a tunnel under Times Square in New York.

Now they had to choose somewhere to start digging. One morning they came across a cocktail-straw factory, set back from the road. They introduced themselves to the owner, concocting an elaborate story about being jazz musicians in need of a rehearsal space. But he guessed what they were up to. He had also escaped from the East and was more than willing to let them use his cellar.

Next, they needed to find a basement in the East to dig to. They chose a friend’s flat, but rather than tell him, they persuaded someone to steal his key and make copies, so the escapees would be able to enter.

Then they started the search for more tunnellers.

This was no easy task. West Berlin was full of spies working for the dreaded Stasi, the East German ministry of state security. It was the most powerful part of the East German government, combining secret police and the intelligence services. Its mission was to know everything – what you thought, who you were married to, who you were sleeping with.

There were even jokes about it: “Why do Stasi officers make such good taxi drivers? Because you get in the car, and they already know your name and where you live.”

They had hundreds of thousands of informants, some of whom had infiltrated government, businesses, hospitals, schools and universities in the West.

Eventually, the tunnellers found three other students they thought they could trust, all of whom had recently escaped from the East: Wolf Schroedter (tall and charming), Hasso Herschel (a Castro-loving revolutionary), and Uli Pfeifer (distraught after his girlfriend had been caught escaping by the Stasi).

Best of all, they were engineering students, so they might have a few ideas about how to dig a tunnel.

Finally, they needed tools. One night they jumped over a wall into a cemetery and stole wheelbarrows, hammers, spades and rakes. Everything was set. On 9 May 1962, just before midnight, digging began at the factory.

“We had no idea where to start,” says Joachim. “We’d never seen a real tunnel. But we’d seen footage of tunnels on TV, ones that had failed, and that gave us ideas about how to dig one.”

Over the next few nights, they dug straight down, 1.3m exactly. Now they could start digging horizontally towards the East. This was the moment they realised how difficult it was going to be.

“When you were down in the tunnel, you had to lie flat on your back,” says Joachim. “You’d point your feet in the direction you were digging, you held onto the spade with both hands, and you’d use your feet to push it down into the clay.”

It would take them hours to dig out a small heap of earth. They’d put it on a cart, and with an old World War Two telephone that Joachim had found, ring through to the cellar to alert them that the cart was ready. Someone would then pull the cart up on a piece of rope.

Before long, they established a steady rhythm, spending hours at the factory, digging and hauling carts of clay. After a few weeks, though, they were exhausted. Their hands were covered in blisters, their backs ached, but they had little to show for it. They hadn’t even reached the border. They needed two things – people and money.

The TV Producer

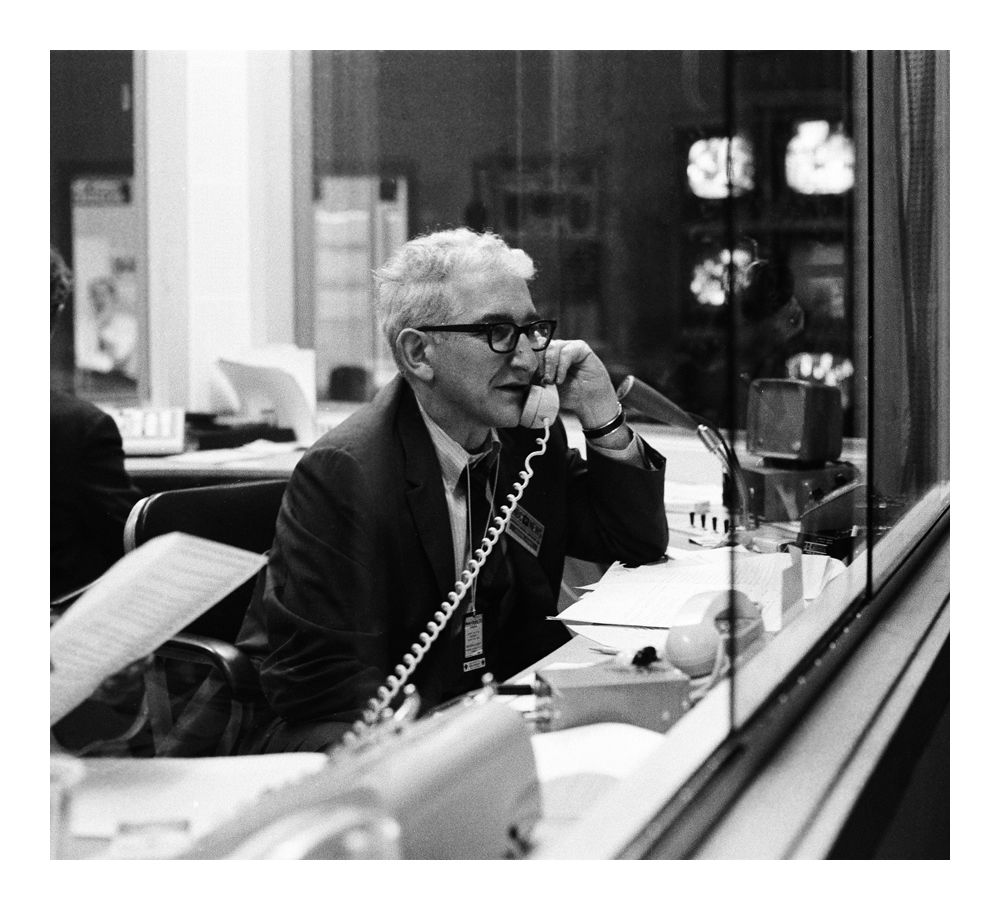

Thousands of miles away in New York, a hotshot TV producer named Reuven Frank was thinking about how to tell the story of Berlin. He’d been there when the wall went up and wanted to explain what was going on beyond the headlines.

He was one of the most powerful figures at the US news network NBC. One morning he had an idea: What if he could find an escape story that was happening right now?

They could film it in real time, every twist and turn, not knowing how it would end. It could revolutionise TV news.

Frank took his idea to the NBC correspondent in Berlin, Piers Anderton, who loved it and began making enquiries.

It was not long before Anderton’s search for tunnellers brought him to the charming engineering student Wolf Schroedter, who was trying to raise money for the diggers.

“We brought him to see the tunnel,” says Schroedter. “He was really impressed. He told us he wanted to film it. And that’s when we told him our conditions – if NBC wanted to film it, they would have to pay us.”

Anderton relayed all this to Frank who agreed straight away. NBC would pay for tools and materials, “and in return we would have the right to film,” says Frank.

And with that, Frank had just made one of the most controversial decisions in the history of TV news – a major US news network had agreed to fund a group of students building an escape tunnel under the Berlin Wall.

The Death Strip

By the end of June 1962, the students had dug around 50m – almost all the way to the border. They’d been digging for 38 days, eight hours a day. With the NBC money, they had bought new tools – enabling them to recruit more people to dig – and bought steel to make a rail line for the cart. The tunnel was soon looking pretty hi-tech, with Joachim its chief inventor. He strung up electric lights, attached a motor to the rails so the cart full of earth would whizz along faster, and he taped hundreds of stove pipes together to bring in fresh air from the outside. Filming all of these contraptions were two Bavarian brothers. There is no sound in the NBC footage because the tunnel was too small for a tape recorder. On one occasion when they were able to bring down a microphone, you can hear a tram, a bus, and footsteps. “It was incredible,” says Joachim. “You could hear everything.” But as they dug further into the East, the sounds above the tunnellers disappeared. Now they were right under the “death strip”, a section of land next to the wall, patrolled by armed border guards who were on the look-out for tunnels.

Theirs wasn’t the first tunnel to be dug under the wall. There had been others, but most had failed. Only a few weeks earlier, border guards had caught two men digging – shots were fired and one was killed, the other badly injured. “The border guards had special listening devices that they’d put on the ground,” says Joachim. “If they heard something, they’d dig a hole and fire a gun into it or throw in dynamite. So as we dug, we knew that at any time, the ground above our heads could suddenly be ripped open.” Sometimes they could even hear the guards talking. “And we knew that if we could hear them, there was a chance they could hear us. So we couldn’t talk anymore when we were in the tunnel.” Fans had to be switched off, which meant it was hard to breathe at the front of the tunnel. All they could hear was the wind and the sound of their own breathing. “Then there were the sounds that you could never work out,” says Joachim. “Was it the Stasi? Were they coming for us?”

One evening, Joachim was digging when he heard a dripping noise. The tunnel had a leak. Within a few hours, water was flowing in. The tunnellers realised a pipe must have burst, and they knew that if the water kept coming, they’d lose the tunnel. They came up with a risky plan – to ask the West Berlin water authorities to fix the pipe. To their surprise, they agreed. But after it was fixed, the tunnel was still waterlogged. It would take months to dry out. They had been so close – just 50m away from the basement in the East. All the people they wanted to get through to, were ready and waiting – Hasso’s sister, Uli’s girlfriend.

The Second Tunnel

It was now July 1962, almost a year since the wall went up. Tripwires had been added, as well as landmines, electric fences, spikes, spotlights, and should these fail to stop an escapee, the border guards were armed with pistols, machine guns, mortars, anti-tank rifles and flame-throwers. But every month, the escapees kept coming. Some hid in cars, others used fake passports. The tunnellers could no longer sit and wait for the tunnel to slowly dry out. Eventually, they heard about another tunnel that had been dug into the East, but left abandoned and unfinished. The students who had planned this other tunnel asked Joachim and the others if they would be interested in joining forces. They could combine their lists of escapees and get them all through at the same time. “It seemed too perfect an opportunity to pass up,” says Joachim. “We were a group of diggers without a tunnel, and here was a tunnel that needed diggers.” They were given just a few details.

The tunnel was meant to emerge underneath a cottage in East Berlin, and about 80 escapees were hoping to crawl through it. A few days later, they went to see the tunnel. “It was a complete shock,” says Joachim. “It was nothing like ours.” Joachim’s tunnel had lights, telephones, motorised pulley systems, air pipes. This one had no lights, no air pumped in, and the ceiling was so low you could hardly crawl. Every time a car went over the road above, clay would trickle down into the tunnel. But they decided to stick with it, enlarging it and digging the final few metres until they were directly under the cottage. The tunnel was ready. Now all they needed was a messenger to pass on details to the escapees. Wolfdieter Sternheimer was another student living in West Berlin. He had heard about the tunnel and had volunteered to help, in return for getting his girlfriend out of the East. Her name was Renate and they had fallen in love after becoming pen-pals and writing letters about “the Beatles and the great questions of life,” he says.

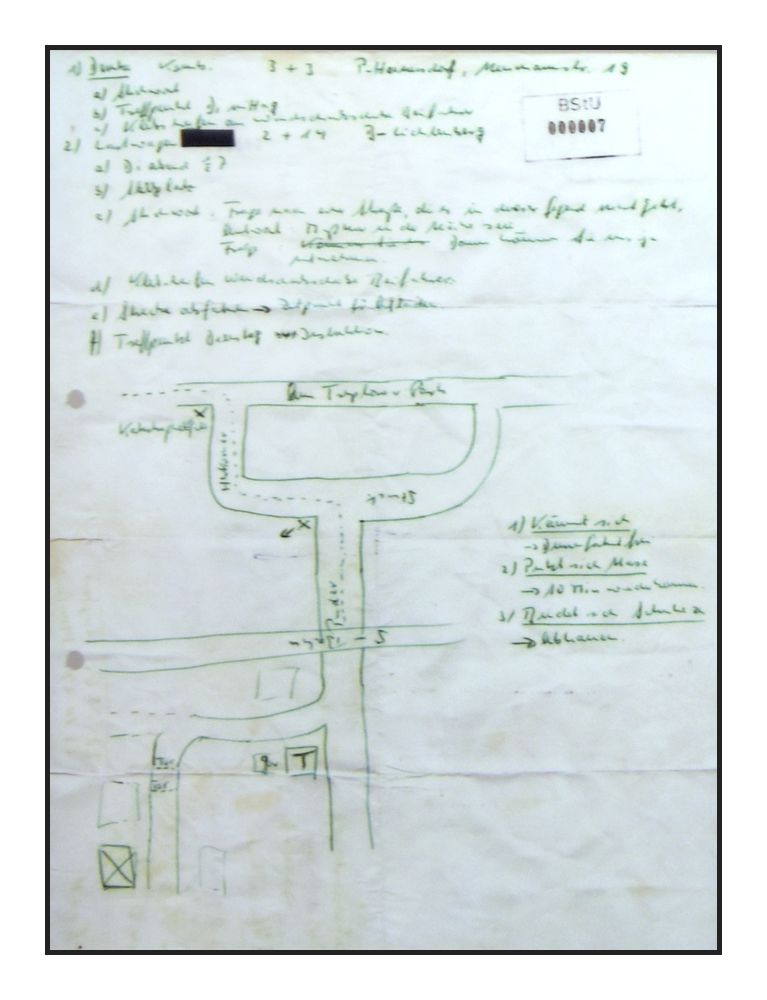

Sternheimer was useful because unlike all the other tunnellers, he was born in West Germany, which meant he could go into the East whenever he liked. Over the next few weeks, he went in and out of East Berlin, updating the escapees. The date of 7 August was fixed. The day before, a meeting of the student organisers was called. Among them was a man Sternheimer says he had never seen before. His name was Siegfried Uhse, and he was a hairdresser. It was Uhse who stepped forward eagerly when a volunteer to go to the East to deliver final instructions was sought. But directly after the meeting, instead of going home, he went to a flat codenamed “Orient” where he met his Stasi handler. Uhse was an informant, who had been recruited six months earlier. The report from that day records what he told his superior: “The breakthrough would happen between 4pm and 7pm” and “100 people were expected.” The Stasi were now onto Joachim’s tunnel – the biggest escape operation so far from West Berlin.

The Trap

Escape day arrived. All over East Berlin, men, women – including Wolfdieter’s fiance, Renate – and children, started to make their way towards the cottage. They set off at different times. Some walked, others took the bus or tram.

Most of them were terrified. They’d hardly slept the night before, spending hours packing and re-packing the one bag they could take with them, squeezing in nappies, photos and clothes. Once they reached the West, this would be all they had to start their new lives with. As they made their way to the cottage, the Stasi machine kicked in. The commander of the border brigade ordered soldiers, an armoured personnel carrier and a water cannon to meet at a base near the cottage. Then, finally, plain-clothes Stasi agents were sent to the cottage. When they got there, they spread out into the streets and waited. The trap was set.

Back at the tunnel, Joachim, Hasso and Uli were preparing for the breakthrough. These engineering students were afraid. They had never done anything like this before and had no idea if they would even be able to hack into the cottage, or what they would find when they did. They collected everything they needed – axes, hammers, drills and radios. They had also managed to get hold of pistols and even an old WW2 machine gun. “We wanted to be able to defend ourselves in case the Stasi were on to us,” says Joachim. Slowly, quietly, they started crawling down the tunnel. When they reached the end, they started hacking into the floor above them. It was now four in the afternoon and above them, on a street outside the cottage, people were arriving. But when there was no chance of escape, Stasi agents suddenly turned on them, bundling them into cars and driving them away.

Underneath them, Joachim, Hasso and Uli were still hacking into the cottage, unaware the operation had been blown. “Then suddenly we heard something over the radio from the West,” says Joachim. “They were shouting at us to come back.” But the tunnellers kept going. “All we could think about were the people coming to the cottage and we didn’t want to let them down,” says Joachim. They carried on hacking into the floor, until finally they broke into the living room. They held a small mirror up so they could see into the room. It was empty except for a few chairs and a sofa. It was eerily quiet – too quiet. But they had come this far and had to go on. They climbed up into the room and Joachim crept towards the window. He peered through the side of a curtain. “I saw this man in civilian clothes, just outside the house, creeping under the window. I knew straight away he was Stasi.”

They were terrified. They knew the operation had been blown, but what they didn’t know was that a group of soldiers was now standing right outside the living room door, Kalashnikovs in their hands. There’s an astonishing moment that’s recorded in a Stasi file (one of more than 2,000 files I read while researching this story, all held in the former Stasi headquarters). The report states that soldiers were about to burst in to the living room when suddenly they heard one of the tunnellers mention a machine gun. They paused and decided to wait for back-up. They knew their Kalashnikovs were no match for a machine gun. That pause saved the lives of the tunnellers. They jumped back through the hole into the tunnel and started crawling as fast as they could back into the West, their bags of tools and weapons swinging against their legs. They knew that at any moment, the soldiers could burst into the room, follow them into the tunnel and shoot after them. It was only a few minutes later when the soldiers rushed into the living room and entered the tunnel, but it was empty. The Stasi agents were too late to catch the tunnellers. But they had something else – dozens of prisoners to interrogate.

The Interrogation

By now, only one person was unaware the operation had been blown – Wolfdieter. He’d been in the East helping out with the operation, and now he was on his way back to the border, excited about seeing Renate. When he arrived at the checkpoint, two men were waiting for him. He knew straight away he had been caught. First, he was questioned by the police. Then they turned him over to the Stasi. They took him to Hohenschönhausen prison, an old Soviet prison now repurposed by the Stasi. “It was the middle of the night,” remembers Wolfdieter. “I was strip-searched, then given prison clothes. And then the interrogation began.”

In the 1950s, the Stasi had been infamous for carrying out physical torture. By the 1960s they were relying more upon techniques for psychological torture. Stasi manuals focusing on how to extract information using these new techniques were published, and senior Stasi officers would teach recruits how to interrogate prisoners at special universities. The psychological pressure began with the prison itself, which was designed to slowly crush the spirit of its inmates. Prisoners weren’t allowed to talk to each other. There was no chatting, no solidarity. In their cells, they had no control over anything – the light switch was on the outside, as was the button to flush the toilet. Then, at some point, the prisoners would be taken to the interrogation room.

“The first interrogation went on for 12 hours,” remembers Wolfdieter. “They don’t have to beat you. You are tired, there’s no water, no food. Nothing.” The transcript of Wolfdieter’s interrogation is 50 pages long. His interrogator asks him a series of questions and then goes back over each one, again and again. A few hours later, a new interrogation starts – the same questions, over and over. Bit by bit, tired, hungry and thirsty, he tells them everything. Wolfdieter was sentenced to seven years’ hard labour. And he wasn’t the only one. Many of those arrested at the tunnel that night were now in prison, even mothers, separated from their children.

The Second Attempt

You would think that after the operation had been blown, with so many arrested and imprisoned, that the tunnellers would give up. They didn’t. They knew the Stasi had no details about their original tunnel and so they decided to try again. This time, they would keep the details tighter and the group of diggers smaller. It was now September 1962, and the original tunnel had dried out enough to allow work to re-start. But before long, it sprang another leak. This time, they were too far into the East for the West German water authorities to fix it. The diggers would either have to abandon the tunnel or break through into a random basement. Using their maps, the tunnellers worked out they were now under Schönholzer Strasse, a street in the East that was so close to the wall it was patrolled by border guards. Tunnelling up there would be a huge risk – it would be noisy, and what’s more, any escapees would have to walk past the border guards to enter the cellar. It was hard to imagine how it could work, but these diggers had proved they were brave and they were determined to give it another go.

The date was set for 14 September. Some students volunteered to go into the East and tell the escapees the new plan. But like last time, they would need a messenger to cross the border on the escape day itself and give signals, so that the East Berliners would know when to go to the tunnel.

Unsurprisingly, after what happened to Wolfdieter, no-one was keen to step forward. But then one of the tunnellers, Mimmo, had an idea – what about his 21-year-old girlfriend, Ellen Schau? Like Wolfdieter, she had a West German passport so she could go in and out of the East, and as a woman, perhaps she would arouse less suspicion? Ellen agreed to do it.

The escapees had been told to go to three different pubs and wait. Once the tunnellers had broken through into the cellar, Ellen was to go to each of these pubs and give a secret signal.

Ellen was filmed as she boarded a train into the East. Wearing a dress, headscarf and sunglasses, she looks like a 60s movie star. You see her check her watch. It’s midday. She turns towards the station and runs up the stairs.

Meanwhile, Joachim and Hasso began hacking into the cellar of an apartment on Schönholzer Strasse. Joachim eventually climbed up into the cellar and unlocked the door to the apartment lobby using a set of skeleton keys.

He needed the number of the apartment they’d dug into. First, he went into the hall. No number there. And he realised the only way to find out was to go outside into the street – the street that was patrolled by border guards.

He opened the front door to the building and saw a group of guards sitting in a hut. They were distracted, so he slipped out into the street. “There was a big number seven just above the door,” he says.

They used their trusty WW2 telephone to get a message to the rest of the team, who were in a West Berlin flat overlooking the wall. A white sheet was draped from the window – Ellen’s signal that the escape was on. From the East, Ellen saw the sheet and went to the first pub to start giving the signals.

“It was really loud,” Ellen remembers. “And when I walked in, the men all turned round and looked at me. The signal was for me to buy a box of matches. So I walked up to the bar, and that’s when I noticed these people staring at me.”

It was a family, sitting at a table. The mother was wearing a dress and high heels, holding her toddler on her lap. Ellen ordered the matches and left. In the next pub she ordered some water – that was the next signal.

When she arrived at the final pub, things didn’t go quite to plan. The signal there was for her to order a coffee, but the waiter said they had run out. “It was a terrible moment,” she says. “How could I give the signal if the pub didn’t have any coffee?”

Instead, she started complaining loudly about the coffee, and ordered a cognac. She drank it, turned around, saw two families waiting and hoped they understood the signal. She left the pub. Her job was done.

As she made her way back to West Berlin, small groups of people started walking towards Shonholzer Strasse. They were doing their best not to stand out, just a few at a time.

Joachim and Hasso were waiting in the cellar, guns in their hands. Just after 18:00, they heard footsteps. “We stood there, hardly breathing, gripping our guns tightly,” says Joachim.

The door opened. The mother from the first pub, Eveline Schmidt, stood there, with her husband and two-year-old daughter. They were helped down into the tunnel. “It was dark,” says Eveline. “There was just one lamp by the entrance. One of the tunnellers took my baby and then I started crawling.”

At the other end, in the West, the two-man NBC film crew were standing at the top of the tunnel shaft. In the footage of this moment, for a long time nothing happens, and then suddenly a white handbag appears. Then there’s a hand, and then, finally, Eveline.

She’s covered in mud, her tights are torn and her feet are bare. She’s lost her shoes somewhere in the tunnel. It’s taken her 12 minutes to crawl through it. She looks up towards the camera, blinking into the light. And then she starts climbing the ladder up into the cellar. Just as she reaches the top, she collapses.

One of the NBC cameramen catches her and helps her to a bench. She sits there, shaking, and then one of the tunnellers brings her baby to her. She bundles her into her arms, nuzzling the nape of her neck.

Over the next hour, more people came. There was Hasso’s sister, Anita, and others – eight-year-olds, 18-year-olds, 80-year-olds. By 23:00, almost everyone on their list had made it through.

The tunnel was filling with water, but one digger was still waiting. His name was Claus, and he was hoping his wife, Inge, might come.

Inge had been sent to a communist prison camp after she was caught trying to escape with him. She’d been pregnant at the time and he hadn’t seen her since.

In the NBC footage, the camera is focused on the tunnel. Suddenly, a woman emerges. Claus pulls her towards him, but she carries on going – she doesn’t recognise her husband in the dark. He looks up after her, then hears another noise coming from the tunnel.

It’s a baby, dressed in white, carried by one of the tunnellers. He’s tiny – only five months old. Claus bends down and gently takes the child, delivering it from the tunnel. It’s a boy, his son, born in a communist prison.

Back at the other end, in the East, Joachim was still in the cellar. Twenty-nine people have made it through. With the water up to his knees, he knew it was time to go. “So many things went through my head,” he says.

“All the things we’d gone through digging it. The leaks, the electric shocks, all the mud, so much mud, the blisters on our hands. Seeing all those refugees come through, I felt the most incredible happiness.”

A few months later, NBC broadcast the film, despite an attempt by President Kennedy’s White House to block it, fearing a diplomatic incident with the Soviet Union.

It was described as without parallel in the history of television. The tunnellers heard that President Kennedy himself watched it and that he had been moved to tears.

And what about the tunnellers? Wolfdieter, the messenger caught by the Stasi, was released from prison after two years. Siegfried Uhse was given one of the Stasi’s top medals for infiltrating the tunnel. Wolf Schroedter and Hasso Herschel worked on other tunnels, and Mimmo’s girlfriend Ellen, the brave courier, wrote a book about her experience.

And, finally, what about Joachim? There’s one final story to tell. A few years after the escape, he fell in love with Eveline, the first woman who came through the tunnel. Her marriage had broken up and 10 years after he rescued her, he married her.

On the wall of their apartment today, there’s a pair of shoes that he picked up a few days after the escape. Little did he know when he found them in the tunnel that these belonged to Annett, Eveline’s daughter. And so the tunnel that Joachim built, which brought 29 hopeful refugees from the East, also brought him a family.

Finally, what about the wall?

At least 140 people were killed at the wall before it was pulled down in November 1989. Right now, more walls are being built, dividing cities and countries, but Joachim says there’s one thing they have in common.

“Wherever there’s a wall, people will try to get over it.” Or, perhaps, he should say, under it.

Helena Merriman tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel right under the feet of Berlin Wall border guards to help friends, family and strangers escape in a BBC Radio 4 podcast.

Прыжок в свободу

(текст с вики)

15 августа 1961 года Шуман был направлен на перекресток улиц Руппинер-штрассе и Бернауэр-штрассе на охрану начатого двумя днями ранее строительства Берлинской стены. На тот момент там существовало только временное заграждение из колючей проволоки высотой около 80 см. Под предлогом проверки заграждения Шуман примял его в одном месте ногой. Заметив его действия, западные немцы с другой стороны закричали ему: «Перепрыгивай!» (нем. Komm über!)…

а подъехавшая полицейская машина остановилась в 10 метрах и открыла дверь, ожидая его. Шуман примеривался некоторое время, затем наконец решился, прыгнул через заграждение и побежал к полицейскому автомобилю, который сразу же забрал его с места происшествия. Фотограф Петер Лайбинг, посланный в тот день к месту строительства стены, также заметил колебания Шумана, понял, что может произойти, и заранее сфокусировал свою камеру на проволочном заграждении. Ему удалось заснять момент прыжка, и эта фотография с тех пор стала одним из наиболее символичных сюжетов холодной войны.

Впоследствии Шуман перебрался из Западного Берлина в Баварию. Там, в городе Гюнцбург, он познакомился со своей будущей женой. Работал автослесарем. Долгие годы Шуман опасался мести со стороны спецслужб ГДР за свой побег и не поддерживал никаких контактов с оставшимися в Саксонии родственниками. После падения Берлинской стены он сказал:

Лишь с 9 ноября 1989 года я чувствую себя действительно свободным.

Страдавший от депрессии Шуман 20 июня 1998 года покончил жизнь самоубийством, повесившись в саду собственного дома.

(4) Прыжок в свободу: rublev.blog — ЖЖ

La construction du mur de Berlin Paris Match