“Давайте считать!” Лейбниц, Ллулл и вычислительное воображение

Three hundred years after the death of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and seven hundred years after the death of Ramon Llull, Jonathan Gray looks at how their early visions of computation and the “combinatorial art” speak to our own age of data, algorithms, and artificial intelligence.

Через триста лет после смерти Готфрида Вильгельма Лейбница и через семьсот лет после смерти Рамона Ллулла Джонатан Грей рассматривает, как их ранние представления о вычислениях и “комбинаторном искусстве” связаны с нашим веком данных, алгоритмов и искусственного интеллекта.

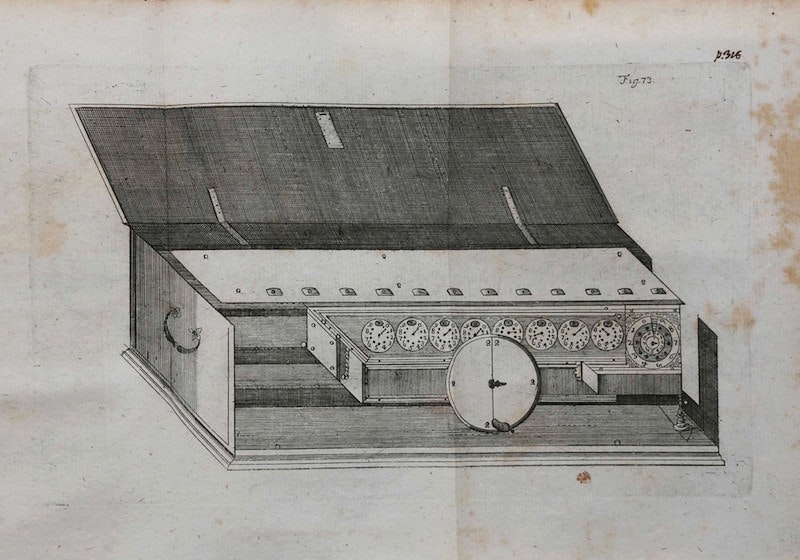

Drawing of Leibniz’s calculating machine, featured as a folding plate in Miscellanea Berolensia ad incrementum scientiarum (1710), the volume in which he first describes his invention — Source. / Рисунок вычислительной машины Лейбница, представленный в виде складной пластины в книге “Miscellanea Berolensia ad incrementum scientiarum” (1710), в которой он впервые описывает свое изобретение – Источник.

Each epoch dreams the one to follow”, wrote the historian Jules Michelet. The passage was later used by the philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin in relation to his unfinished magnum opus, The Arcades Project, which explores the genesis of life under late capitalism through a forensic examination of the “dreamworlds” of nineteenth-century Paris.1 In tracing the emergence of the guiding ideals and visions of our own digital age, we may cast our eyes back a little earlier still: to the dreams of seventeenth-century polymath Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.

Каждая эпоха видит во сне ту, которая последует за ней”, – писал историк Жюль Мишеле. Позже этот отрывок был использован философом и культурным критиком Вальтером Беньямином в связи с его незаконченным magnum opus “Проект Аркады”, который исследует генезис жизни при позднем капитализме через криминалистическое исследование “мира грез” Парижа XIX века.1 Прослеживая возникновение руководящих идеалов и видений нашей собственной цифровой эпохи, мы можем обратить свой взор еще немного раньше: к мечтам эрудита XVII века Готфрида Вильгельма Лейбница.

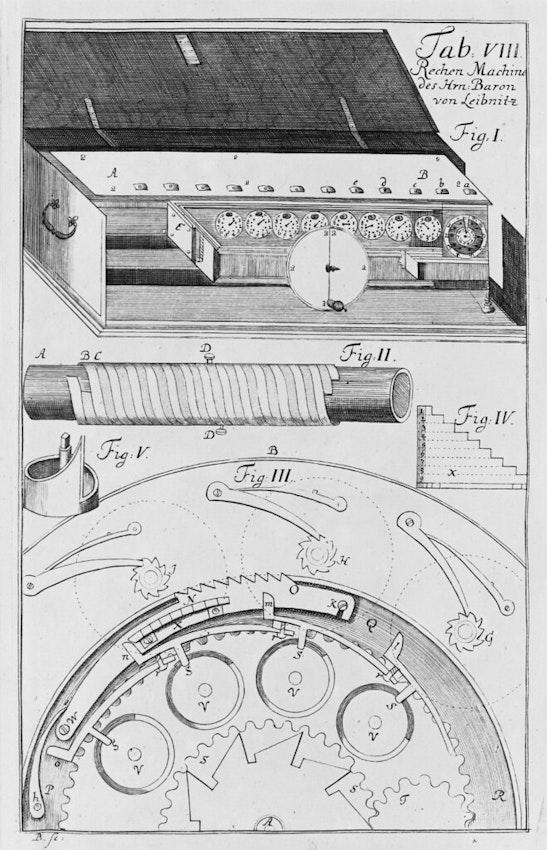

There was a resurgence of interest in Leibniz’s role in the history of computation after workmen fixing a leaking roof discovered a mysterious machine discarded in the corner of an attic at the University of Göttingen in 1879. With its cylinders of polished brass and oaken handles, the artefact was identified as one of a number of early mechanical calculating devices that Leibniz invented in the late seventeenth century. Supported by a network of professors, preachers, and friends — and developed with the technical assistance of a series of itinerant and precariously employed clockmakers, mechanics, artisans, and even a butler — Leibniz’s instrument aspired to provide less function than even the most basic of today’s calculators. Through an intricate system of different sized wheels, the hand-crank operated device modestly expanded the repertoire of possible operations to include multiplication and division as well as addition and subtraction.2

Интерес к роли Лейбница в истории вычислений возродился после того, как в 1879 году рабочие, чинившие протекающую крышу, обнаружили в углу чердака Геттингенского университета загадочную машину, выброшенную на пол. Артефакт с цилиндрами из полированной латуни и дубовыми ручками был идентифицирован как одно из ранних механических вычислительных устройств, изобретенных Лейбницем в конце XVII века. Поддерживаемый сетью профессоров, проповедников и друзей – и созданный при технической помощи ряда странствующих и нестабильно работающих часовщиков, механиков, ремесленников и даже дворецкого – инструмент Лейбница стремился обеспечить меньшее количество функций, чем даже самые простые из современных калькуляторов. Благодаря сложной системе колес разного размера, устройство с ручным приводом скромно расширяло репертуар возможных операций, включая умножение и деление, а также сложение и вычитание.2

Illustration of Leibniz’s calculating machine (based on the sketch above), featuring in Theatrum arithmetico-geometricum, das ist … (1727) by Jacob Leupold — Source. / Иллюстрация вычислительной машины Лейбница (по эскизу выше), представленная в книге “Theatrum arithmetico-geometricum, das ist …” (1727). (1727), автор Якоб Лейпольд – Источник.

Three centuries before Douglas Engelbart’s “Mother of All Demos” received a standing ovation in 1968, Leibniz’s machine faltered through live demonstrations in London and Paris.3 Costing a small fortune to construct, it suffered from a series of financial setbacks and technical issues. The Royal Society invited Leibniz to come back once it was fully operational. There is even speculation that – despite Leibniz’s rhetoric spanning an impressive volume of letters and publications – the machine never actually worked as intended.4 Nevertheless, the instrument exercised a powerful grip on the imagination of later technicians. Leibniz’s machine became part of textbooks and industry narratives about the development of computation. It was retrospectively integrated into the way that practitioners envisaged the history of their work. IBM acquired a functioning replica for their “antiques attic” collection. Scientist and inventor Stephen Wolfram credits Leibniz with anticipating contemporary projects by “imagining a whole architecture for how knowledge would … be made computational”.5 Norbert Wiener calls him the “patron saint” of cybernetics.6 Another recent writer describes him as the “godfather of the modern algorithm”.7 While Leibniz made groundbreaking contributions towards the modern binary number system as well as integral and differential calculus,8 his role in the history of computing amounts to more than the sum of his scientific and technological accomplishments. He also advanced what we might consider a kind of “computational imaginary” — reflecting on the analytical and generative possibilities of rendering the world computable.

За три столетия до того, как “Мать всех демонстраций” Дугласа Энгельбарта получила овацию в 1968 году, машина Лейбница потерпела неудачу во время демонстрации в Лондоне и Париже.3 Стоившая целое состояние, она страдала от ряда финансовых неудач и технических проблем. Королевское общество пригласило Лейбница вернуться, когда машина будет полностью готова к работе. Существует даже предположение, что, несмотря на риторику Лейбница, выраженную во внушительном объеме писем и публикаций, машина никогда не работала так, как было задумано.4 Тем не менее, прибор оказал сильное влияние на воображение последующих техников. Машина Лейбница стала частью учебников и промышленных повествований о развитии вычислений. Она была ретроспективно интегрирована в то, как специалисты-практики представляли себе историю своей работы. Компания IBM приобрела действующую копию для своей коллекции “антиквариата на чердаке”. Ученый и изобретатель Стивен Вольфрам считает, что Лейбниц предвосхитил современные проекты, “представив целую архитектуру того, как знания… будут сделаны вычислительными”. Норберт Винер называет его “святым покровителем” кибернетики.6 Еще один недавний автор называет его “крестным отцом современного алгоритма”. Хотя Лейбниц внес новаторский вклад в создание современной двоичной системы счисления, а также интегрального и дифференциального исчисления,8 его роль в истории вычислений – это нечто большее, чем сумма его научных и технологических достижений. Он также развил то, что мы можем считать своего рода “вычислительным воображением” – размышления об аналитических и генеративных возможностях преобразования мира в вычислимый.

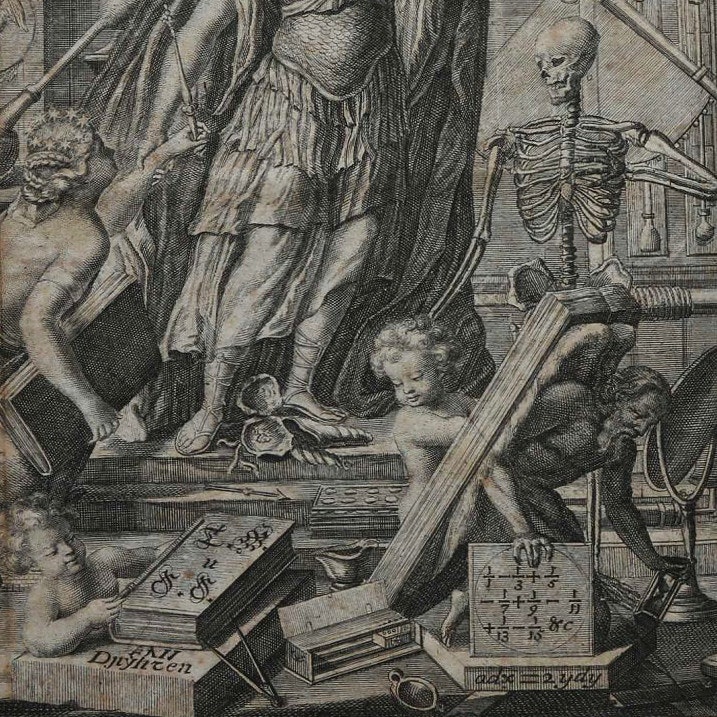

Detail from the frontispiece to Miscellanea Berolensia ad incrementum scientiarum (1710). At the bottom of the image can be seen Leibniz’s calculating machine, the first description of which features in the volume — Source. / Деталь с фронтисписа к “Miscellanea Berolensia ad incrementum scientiarum” (1710). В нижней части изображения видна вычислительная машина Лейбница, первое описание которой представлено в этом томе

A diagram of I Ching hexagrams owned by Leibniz, given to him by the French Jesuit Joachim Bouvet, and to which Leibniz has added Arabic numerals. Leibniz saw immediate parallels between the I Ching and his own work on the characteristica univeralis – and took this as confirmation of universal truth, independently discovered — Source. / Диаграмма гексаграмм И-Цзин, принадлежавшая Лейбницу, подаренная ему французским иезуитом Иоахимом Буве, к которой Лейбниц добавил арабские цифры. Лейбниц сразу же увидел параллели между “И цзин” и своей собственной работой о характеристике универсума – и воспринял это как подтверждение универсальной истины, открытой независимо от него

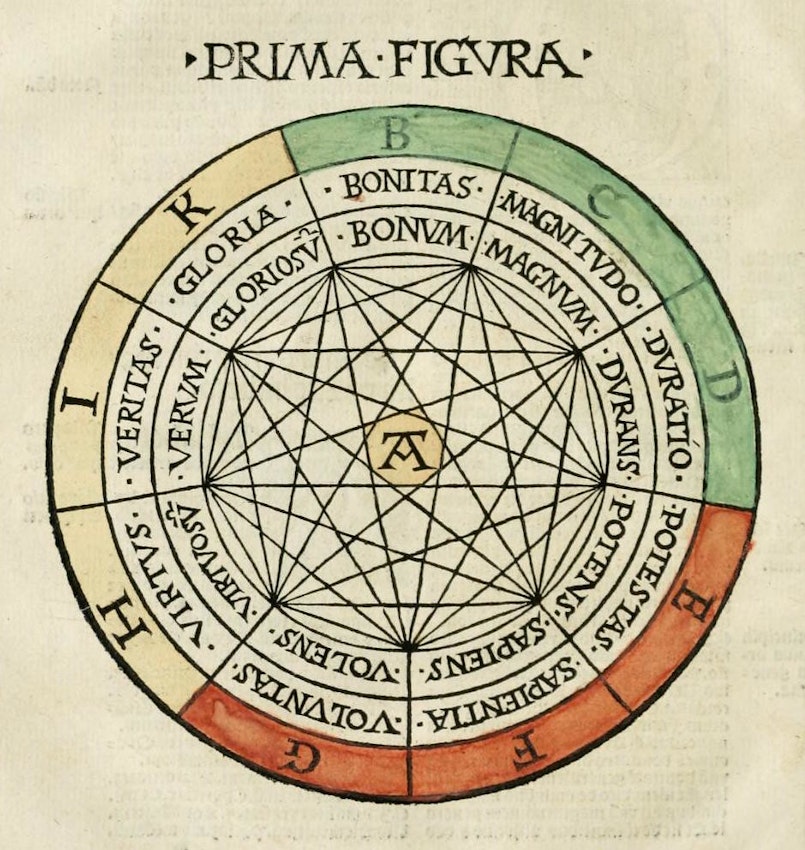

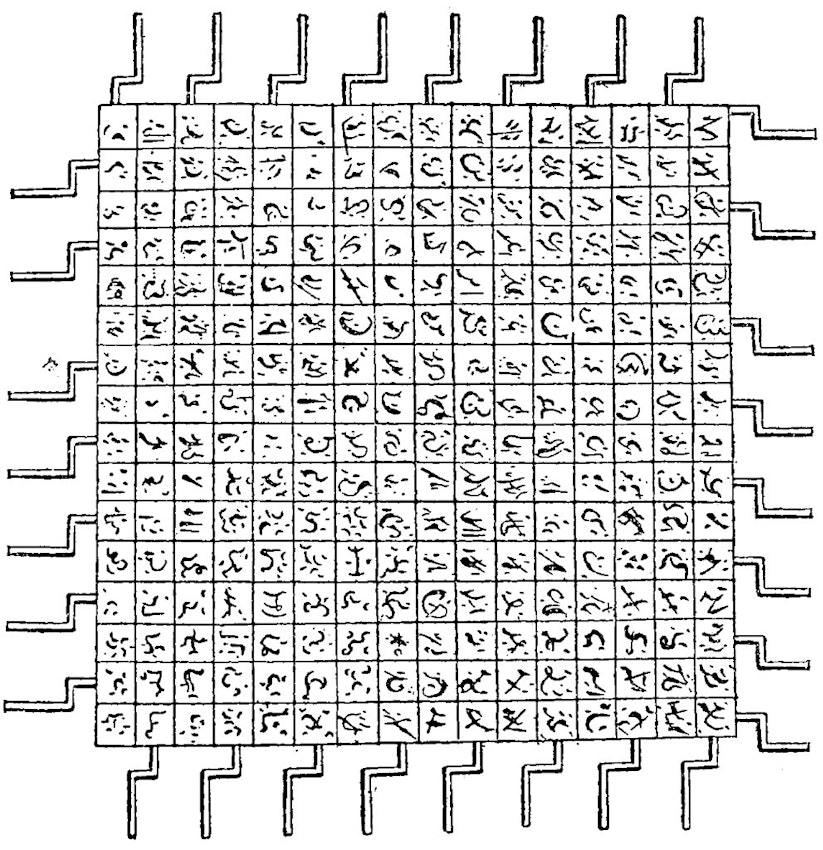

Leibniz’s interest in this area can be traced back to his 1666 Dissertatio De Arte Combinatoria — an extended version of his doctoral dissertation in which he explores what was known as the “art of combinations” (or “combinatorial art”), a method which would enable its practitioners to generate novel ideas and inventions, as well as to analyse and decompose complex and difficult ideas into more simple elements. Describing it as the “mother of all inventions” which would lead to “the discovery of all things”, he sought to demonstrate the widespread applicability of this art to advance human endeavour in areas as diverse as law and logic, music and medicine, physics and politics. Leibniz’s broader vision of the power of logical calculation was inspired by many thinkers — from the logical works of Aristotle and Ramus to Thomas Hobbes’ proposal to equate reasoning with computation. But Leibniz’s curiosity around the art of combinations per se was sparked by a group called the “Herborn Encyclopaedists” through whom he became acquainted with the works of Ramon Llull, a Majorcan philosopher, logician, and mystical thinker who is thought to have died seven centuries ago, in 1316.9 Llull’s Ars magna (or “ultimate general art”) from 1308 outlines a form of analysis and argumentation based on working with different permutations of a small number of fundamental attributes. Llull sought to create a universal tool for helping to convert people to the Christian faith through logical argumentation. He proposed eighteen fundamental general principles (“Goodness, Greatness, Eternity, Power, Wisdom, Will, Virtue, Truth, Glory, Difference, Concordance, Contrariety, Beginning, Middle, End, Majority, Equality, and Minority”), accompanied by a set of definitions, rules, and figures in order to guide the process of argumentation, which is organised around different permutations of the principles. The art was to be used to generate and address questions such as “Is eternal goodness concordant?”, “What does the difference of eternal concordance consist of?”, or “Can goodness be great without concordance?”

Интерес Лейбница к этой области можно проследить по его “Dissertatio De Arte Combinatoria” 1666 года – расширенной версии его докторской диссертации, в которой он исследует то, что было известно как “искусство комбинаций” (или “комбинаторное искусство”), метод, позволяющий практикам генерировать новые идеи и изобретения, а также анализировать и разлагать сложные и трудные идеи на более простые элементы. Описывая его как “мать всех изобретений”, которая приведет к “открытию всех вещей”, он стремился продемонстрировать широкую применимость этого искусства для развития человеческих усилий в таких различных областях, как право и логика, музыка и медицина, физика и политика. Более широкое видение Лейбницем возможностей логического расчета было вдохновлено многими мыслителями – от логических работ Аристотеля и Рамуса до предложения Томаса Гоббса приравнять рассуждения к вычислениям. Но любопытство Лейбница к искусству комбинаций как таковому было вызвано группой “герборнских энциклопедистов”, через которую он познакомился с работами Рамона Ллулла, майоркского философа, логика и мистического мыслителя, который, как считается, умер семь веков назад, в 1316 году.9 В сочинении Ллулла Ars magna (или “высшее общее искусство”) 1308 года описывается форма анализа и аргументации, основанная на работе с различными перестановками небольшого числа фундаментальных атрибутов. Ллулл стремился создать универсальный инструмент для обращения людей в христианскую веру с помощью логической аргументации. Он предложил восемнадцать фундаментальных общих принципов (“Добро, Величие, Вечность, Сила, Мудрость, Воля, Добродетель, Истина, Слава, Различие, Согласие, Противоречие, Начало, Середина, Конец, Большинство, Равенство и Меньшинство”), сопровождаемых набором определений, правил и фигур, чтобы направлять процесс аргументации, организованный вокруг различных перестановок этих принципов. Это искусство должно было использоваться для создания и решения таких вопросов, как “Согласуется ли вечное добро?”, “В чем состоит различие вечного согласования?” или “Может ли добро быть великим без согласования?”.

Diagram featured in a 16th-century edition of Ramon Llull’s Ars Magna (1517) — Source.

Llull held that this art could be used to “banish all erroneous opinions” and to arrive at “true intellectual certitude removed from any doubt”. He drew in turn on the medieval Arabic zairja, an algorithmic process of “letter magic” for calculating truth on the basis of a finite number of elements. Its practitioners would give advice or make predictions on the basis of interpretations of strings of letters resulting from a calculation.10 Llull’s experimentation channelled this procedural conception of reasoning, and was drawn upon by the intellectual milieu in which Leibniz developed his early ideas. While critical towards the details of Llull’s proposed categories and procedures, Leibniz was taken with his overarching vision of the combinatorial art. He drew two key aspirations from Llull’s work: the idea of fundamental conceptual elements, and the idea of a method through which to combine and calculate with them. The former would enable us to reformulate more complex ideas in terms of simpler ones (for “everything which exists or which can be thought”, Leibniz wrote, “must be compounded of parts”).11 The latter would enable us to reason with these elements precisely and without error, as well as generate new insights and ideas.

Ллулл считал, что это искусство может быть использовано для “изгнания всех ошибочных мнений” и достижения “истинной интеллектуальной уверенности, лишенной всяких сомнений”. В свою очередь, он опирался на средневековую арабскую заиржу – алгоритмический процесс “магии букв” для вычисления истины на основе конечного числа элементов. Практиковавшие ее люди давали советы или делали предсказания на основе интерпретации строк, составленных из букв и полученных в результате вычислений. Эксперименты Ллулла отражали эту процедурную концепцию рассуждений, и они были использованы интеллектуальной средой, в которой Лейбниц развивал свои ранние идеи. Хотя Лейбниц критически относился к деталям предложенных Ллуллом категорий и процедур, его всеобъемлющее видение комбинаторного искусства было воспринято Лейбницем. Из работы Ллулла он почерпнул два ключевых стремления: идею фундаментальных концептуальных элементов и идею метода, с помощью которого их можно комбинировать и вычислять. Первое позволит нам переформулировать более сложные идеи в терминах более простых (ведь “все, что существует или может быть мыслимо, – писал Лейбниц, – должно быть составлено из частей”). Второе позволит нам точно и безошибочно рассуждать с помощью этих элементов, а также генерировать новые мысли и идеи.

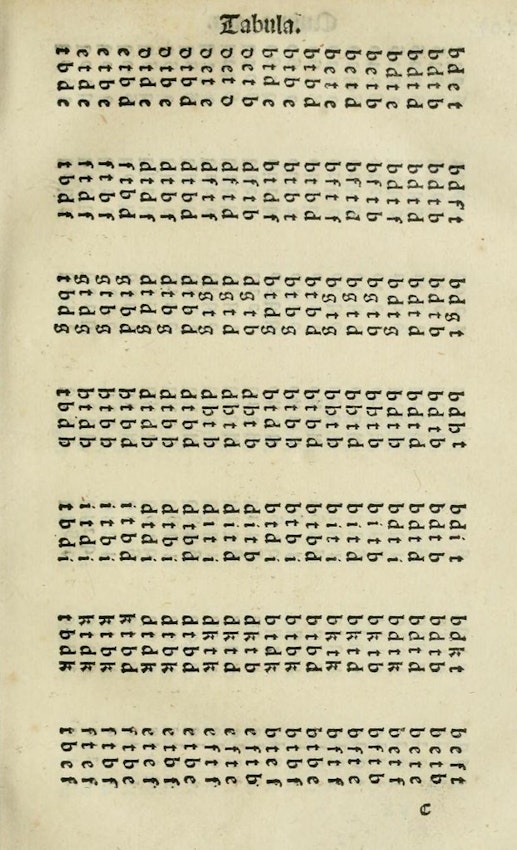

Page of letter combinations from 16th-century edition of Ramon Llull’s Ars Magna (1517) — Source. / Страница буквенных комбинаций из издания 16 века “Ars Magna” Рамона Ллулла (1517)

Just as all words in a language could be represented by the comparatively small number of letters in an alphabet, so the whole world of nature and thought could be considered in terms of a number of fundamental elements — an “alphabet of human thought”. By reformulating arguments and ideas in terms of a characteristica universalis, or universal language, all could be rendered computable. The combinatorial art would not only facilitate such analysis, but would also provide means to compose new ideas, entities, inventions, and worlds. Leibniz spared no modesty in promoting the art and the various initiatives associated with it for which he hoped to raise funds from prospective patrons. He presented his project as being the world’s most powerful instrument, an end to all argument, one of humanity’s most wonderful inventions (fulfilling a timeless dream shared by everyone from the Pythagoreans to the Cartesians); the ultimate source of answers to some of the world’s most complex and difficult theological, moral, legal, or scientific questions; and a foolproof means to converting people to Christianity and propagating the faith, amongst other things. In support of his project he argued that “no man who is not a prophet or a prince can ever undertake anything of greater good to mankind or more fitting for the divine glory”, and that “nothing could be proposed that would be more important for the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith”.12 In a 1679 letter to one of his patrons, Johann Friedrich, he described his project of the universal language as “the great instrument of reason, which will carry the forces of the mind further than the microscope has carried those of sight”. Later he wrote:

Как все слова в языке могут быть представлены сравнительно небольшим количеством букв в алфавите, так и весь мир природы и мысли может быть рассмотрен в терминах ряда фундаментальных элементов – “алфавита человеческого мышления”. Переформулировав аргументы и идеи в терминах characteristica universalis, или универсального языка, все можно было бы сделать вычислимым. Комбинаторное искусство не только облегчило бы такой анализ, но и дало бы средства для создания новых идей, сущностей, изобретений и миров. Лейбниц не жалел скромности, рекламируя искусство и различные инициативы, связанные с ним, на которые он надеялся собрать средства у потенциальных меценатов. Он представлял свой проект как самый мощный в мире инструмент, конец всех споров, одно из самых замечательных изобретений человечества (исполнение вечной мечты, которую разделяли все – от пифагорейцев до картезианцев); конечный источник ответов на самые сложные и трудные богословские, моральные, юридические и научные вопросы; надежное средство для обращения людей в христианство и распространения веры и т.д. и т.п. В поддержку своего проекта он утверждал, что “ни один человек, не являющийся пророком или князем, не может предпринять ничего более полезного для человечества или более подходящего для божественной славы”, и что “не может быть предложено ничего более важного для Конгрегации распространения веры”.12 В письме 1679 года одному из своих покровителей, Иоганну Фридриху, он описал свой проект универсального языка как “великий инструмент разума, который перенесет силы разума дальше, чем микроскоп перенес силы зрения”. Позже он писал:

The only way to rectify our reasonings is to make them as tangible as those of the Mathematicians, so that we can find our error at a glance, and when there are disputes among persons, we can simply say: Let us calculate, without further ado, to see who is right.13

Единственный способ исправить наши рассуждения – сделать их такими же осязаемыми, как у математиков, чтобы мы могли с первого взгляда найти свою ошибку, а когда между людьми возникают споры, мы могли просто сказать: Давайте посчитаем без лишних слов, чтобы узнать, кто прав.

Diagram included at the end of Leibniz’s dissertation on the art of combinations — Source.

Ultimately he hoped that a perspicuous thought language of “pure” concepts, combined with formalised processes and methods akin to those used in mathematics, would lead to the mechanisation and automation of reason itself. By means of new artificial languages and methods, our ordinary and imperfect ways of reasoning with words and ideas would give way to a formal, symbolic, rule-governed science — conceived of as a computational process. Disputes, conflict, and grievances arising from ill-formed opinions, emotional hunches, biases, prejudices, and misunderstandings would give way to consensus, peace, and progress.

Jonathan Swift’s satirical classic Gulliver’s Travels (1726) parodied the mechanical conception of invention advanced by Llull and Leibniz. In the fictional city of Lagado, the protagonist encounters a device known as “the engine”, which is intended by its inventor to enable anyone to “write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, laws, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study”:

He then led me to the frame, about the sides, whereof all his pupils stood in ranks. It was twenty feet square, placed in the middle of the room. The superfices was composed of several bits of wood, about the bigness of a die, but some larger than others. They were all linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered, on every square, with paper pasted on them; and on these papers were written all the words of their language, in their several moods, tenses, and declensions; but without any order. The professor then desired me “to observe; for he was going to set his engine at work.” The pupils, at his command, took each of them hold of an iron handle, whereof there were forty fixed round the edges of the frame; and giving them a sudden turn, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed. He then commanded six-and-thirty of the lads, to read the several lines softly, as they appeared upon the frame; and where they found three or four words together that might make part of a sentence, they dictated to the four remaining boys, who were scribes. This work was repeated three or four times, and at every turn, the engine was so contrived, that the words shifted into new places, as the square bits of wood moved upside down.14

The people of Lagado’s “engine” from Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, as illustrated in The Prose Works of Jonathan Swift, DD, Volume 8 (1899) — Source.

The mechanical, combinatorial approach to cultural creation that Swift treated as an absurd caricature became a productive experimental technique for later writers, artists, and musicians — from the permutational works of American composer John Cage, to the generative poetic experiments of the French literary group Oulipo, to more recent procedural approaches of digital and software art.15 Moreover, the mechanization and externalization of reasoning processes exhibited by machine learning technologies and algorithms has not only become socially and culturally productive, but economically lucrative for today’s silicon empires.

There are few contenders in the history of philosophy to rival the optimism that Leibniz had for his project as a kind of panacea. Many of the ideas of his youth never left him. In a 1714 letter, two years before his death, he laments that he was unable to make more progress:

I should venture to add that if I had been less distracted, or if I were younger or had talented young men to help me, I should still hope to create a kind of spécieuse générale, in which all truths of reason would be reduced to a kind of calculus. At the same time this could be a kind of universal language or writing, though infinitely different from all such languages which have thus far been proposed, for the characters and the words themselves would give directions to reason, and the errors (except those of fact) would be only mistakes in calculation.16

As ever more aspects of earthly life are rendered quantifiable, harvested into clouds, funneled into algorithmic engines — leading to what has been called “planetary-scale computation” — these dreams of the vast creative and emancipatory possibilities of procedural reasoning processes endure.17 The initial trickles of Llull’s and Leibniz’s arcane combinatorial fantasies have gradually given way to ubiquitous computational technologies, practices, and ideals which are interwoven into the fabric of our worlds — the broader consequences of which are still unfolding around us. The objects of their embryonic faith have become the living a priori of the digital age — providing the conditions of possibility for our experience and our reflection, our genres of deliberation, our forms of sociality, and our institutions of judgement — regardless of whether or not the machines operate in the ways that we imagine.

Public Domain Works

- Ars MagnaRamon Llull1517TEXTS

- The Philosophical Works of LeibnitzGottfried Wilhelm Leibniz1890TEXTS

- A System of TheologyGottfried Wilhelm Leibniz1850TEXTS

Further Reading

- Leibniz: An Intellectual BiographyBy Maria Rosa AntognazzaIn this first intellectual biography of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), Maria Rosa Antognazza surveys the full range of the philosopher’s interests and activities and offers a unified portrait of a unique thinker, identifying the master project that inspired and coordinated his huge range of apparently miscellaneous endeavors.More Info and Buy

- The Search for the Perfect LanguageBy Umberto EcoIn this tour de force of scholarly investigation, Eco explores the idea that there once existed a language which was able to express the essence of all possible things and concepts; an idea which has engaged some of the greatest thinkers and mystics over the last 2000 years.More Info and Buy

Books link through to Amazon who will give us a small percentage of sale price (ca. 4.5%). Discover more recommended books in our dedicated PDR Recommends section of the site.

Jonathan Gray is Prize Fellow at the Institute for Policy Research, University of Bath where he is writing a book on Data Worlds. He is also Research Associate at the Digital Methods Initiative, University of Amsterdam; Research Associate at the médialab at Sciences Po; and Tow Fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Columbia University. He is Senior Advisor at Open Knowledge International and cofounder of The Public Domain Review. More about him can be found at jonathangray.org and he is on Twitter at @jwyg.